Quality of Patient Engagement Activities in Health Economics and Outcomes Research: Insights From the ISPOR Community

Samuel Llewellyn, MPH, Vitaccess, London, England, United Kingdom; Nan Qiao, PhD, MPH, MSc, MBBS, Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ, USA; Prajakta Masurkar, PhD, MPharm, Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; Angie Botto-van Bemden, PhD, Musculoskeletal Research International, Holiday, FL, USA; Jessica Roydhouse, PhD, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia; Eleanor Perfetto, MS, RPh, PhD, University of Maryland Baltimore Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department, Venice, FL, USA

Introduction

Patient centricity is increasingly recognized as important in health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) and is one of the ISPOR 2024-2025 Top 10 HEOR Trends.1 Patient engagement is a critical component of patient-centered research and is defined as “the active, meaningful, and collaborative interaction between patients and researchers across all stages of the research process, where research decision making is guided by patients’ contributions as partners, recognizing their specific experiences, values, and expertise.”2 However, simply stating an activity is “patient-centered” or involves “patient engagement” does not provide enough information for readers and researchers to assess the quality of patient engagement. There is growing interest in measuring and evaluating the quality of patient-engagement activities. For example, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), in addition to updating their Foundational Expectations for Partnerships, recently released a call for applications to measure and test engagement approaches.3,4 Industry is also increasingly recognizing the importance of adopting patient-centric approaches and making their efforts more focused on meeting patients’ needs and preferences.5

ISPOR’s Patient-Centered Special Interest Group (SIG) aims to facilitate the engagement and partnership with patients (and families and caregivers) in all stages of health-related research and care delivery in order to improve healthcare access and patient outcomes.6 To achieve this goal, the SIG surveyed its members as well as those of closely related SIGs (eg, Clinical Outcome Assessment and Rare Disease) with the objectives of understanding member experiences with patient engagement, encountered challenges and facilitators to engagement, and assessing engagement quality.

In this article, we present the survey results and discuss the implications of these findings for the HEOR community.

"However, simply stating an activity is “patient-centered” or involves “patient engagement” does not provide enough information for readers and researchers to assess the quality of patient engagement."

Survey of ISPOR membership: Measuring and evaluating the quality of patient engagement activities

The survey was developed by the leadership team of the Patient-Centered SIG and underwent review by ISPOR members, including those with experience working in patient-centered outcomes research. The survey was emailed to members of ISPOR’s Patient-Centered, Clinical Outcome Assessment, and Rare Disease SIGs in August 2023. The survey comprised 23 questions, covering the following dimensions through a combination of closed- and open-ended responses:

- Member experiences with engagement activities

- Facilitators encountered

- Challenges encountered

- Experience with assessing engagement quality.

Respondent demographic and research work-setting descriptors were also collected. Responses were collected anonymously. The initial email was sent with 2 follow-up reminders to encourage responses.

Results

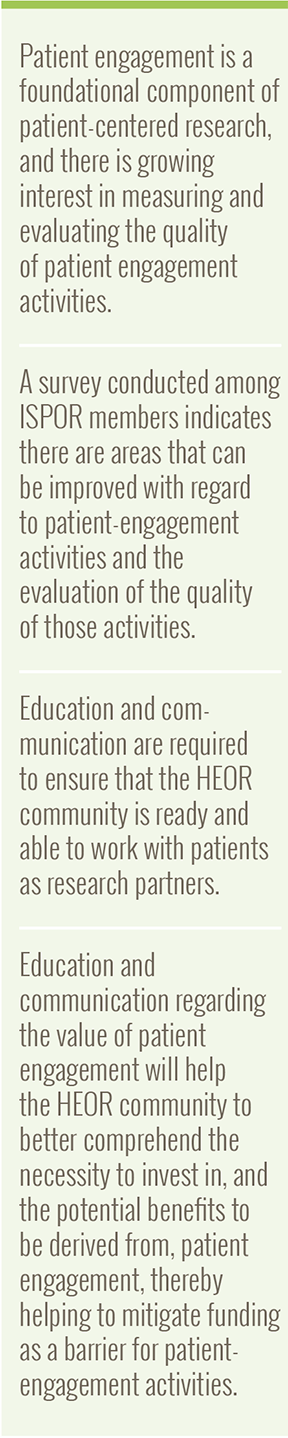

The distribution of perspectives covered by survey participants (n=103, see Figure 1) was generally similar to the overall ISPOR membership.

The survey respondents identified their primary geographic region of interest as follows: Global (36.9%), North America (31.1%), and Asia Pacific (including Oceania) (14.6%). The remaining responses collectively comprised Western Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America (17.5%).

Figure 1. Professional areas of practice of survey respondents

Member experiences with engagement activities

Survey results showed that a large majority of respondents (76.7%) indicated their current work to be “patient-centered,” while the remaining respondents either felt unsure or did not consider their work to be patient-centered. Nearly three-quarters of respondents (73.8%) reported they had engaged patients in their research at some point.* Of the 74 respondents, most (77%) reported that they currently engaged patients in their research.

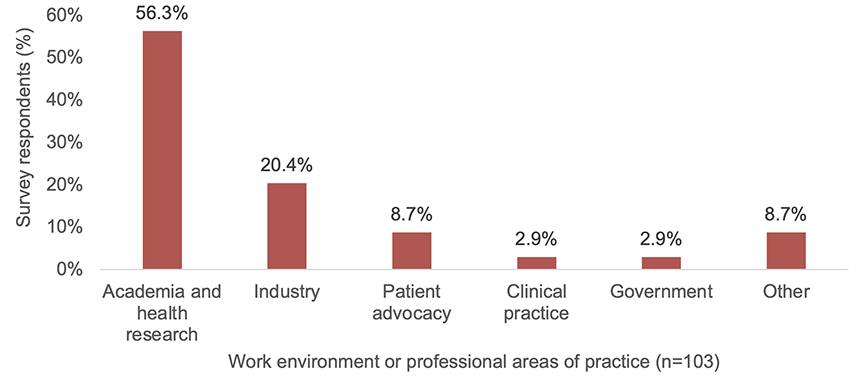

The survey provided insights into the primary attributes of patient-centered research, as perceived by the majority of respondents. These include a focus on outcomes that are important to patients (79.6%), and the collection of patient experience, preferences, or opinions through methods such as focus groups and interviews (73.8%). The most essential attribute of patient-centered research, involving patients as research partners, received only 45.6% of the votes. Figure 2 illustrates these findings.

The survey findings highlighted the most frequently reported, important aspects of patient engagement in research. Specifically, “Representativeness/diversity of patients (including patients as research partners)” emerged as the most crucial aspect, cited by 70% of respondents. “Studies guided by patient experience data from surveys, focus groups, and interviews” (58.3%), and “Including patients throughout all stages of research from ideation or planning through to dissemination/post-market surveillance” (57.3%) followed.

Figure 2. Primary characteristics of “patient-centered” research; respondents could select up to 3 responses

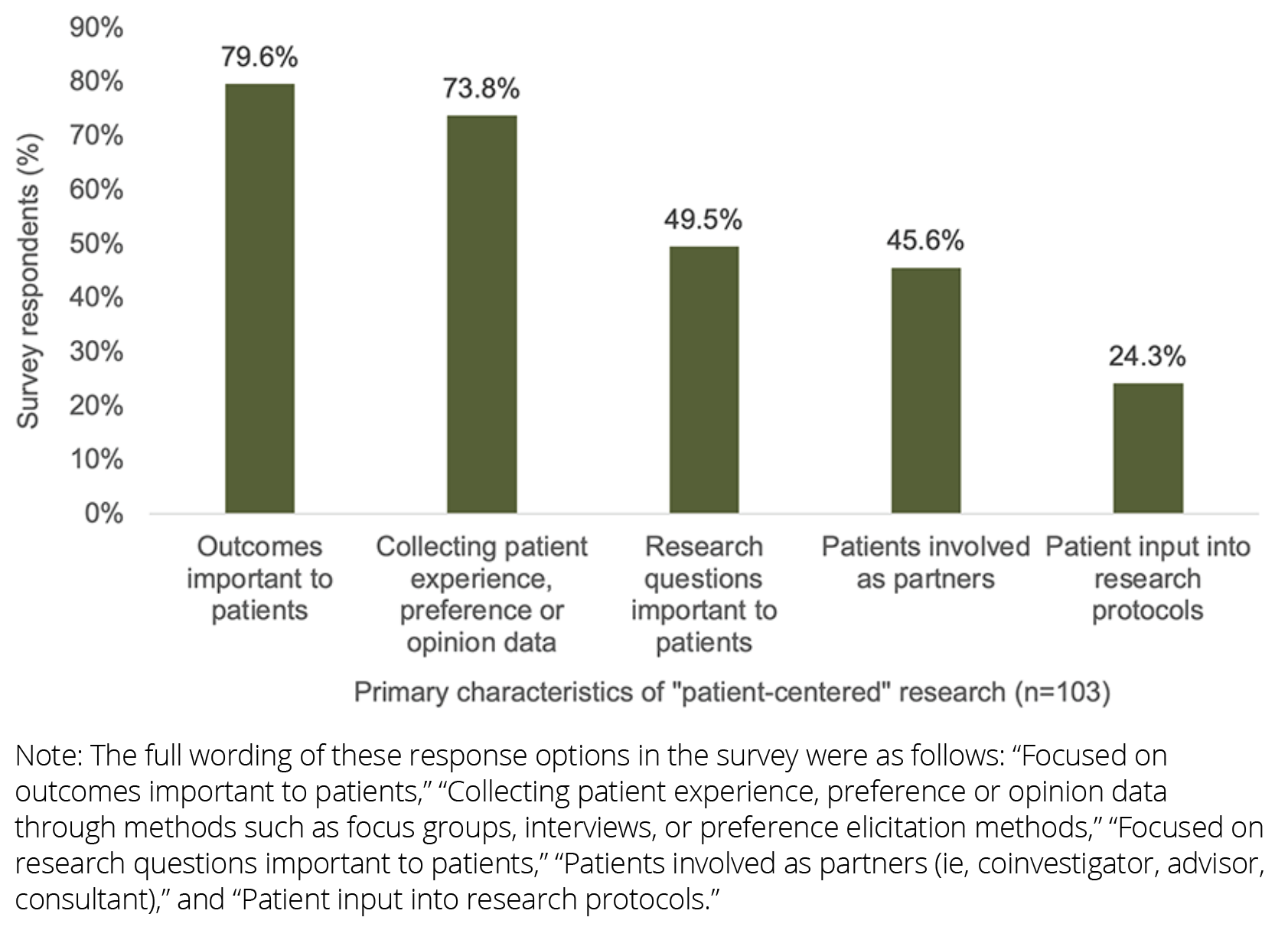

Facilitators encountered

The survey revealed several key facilitators to engaging with patients in research. These results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Facilitators encountered when engaging patients (n=74); respondents could select multiple responses

Challenges encountered

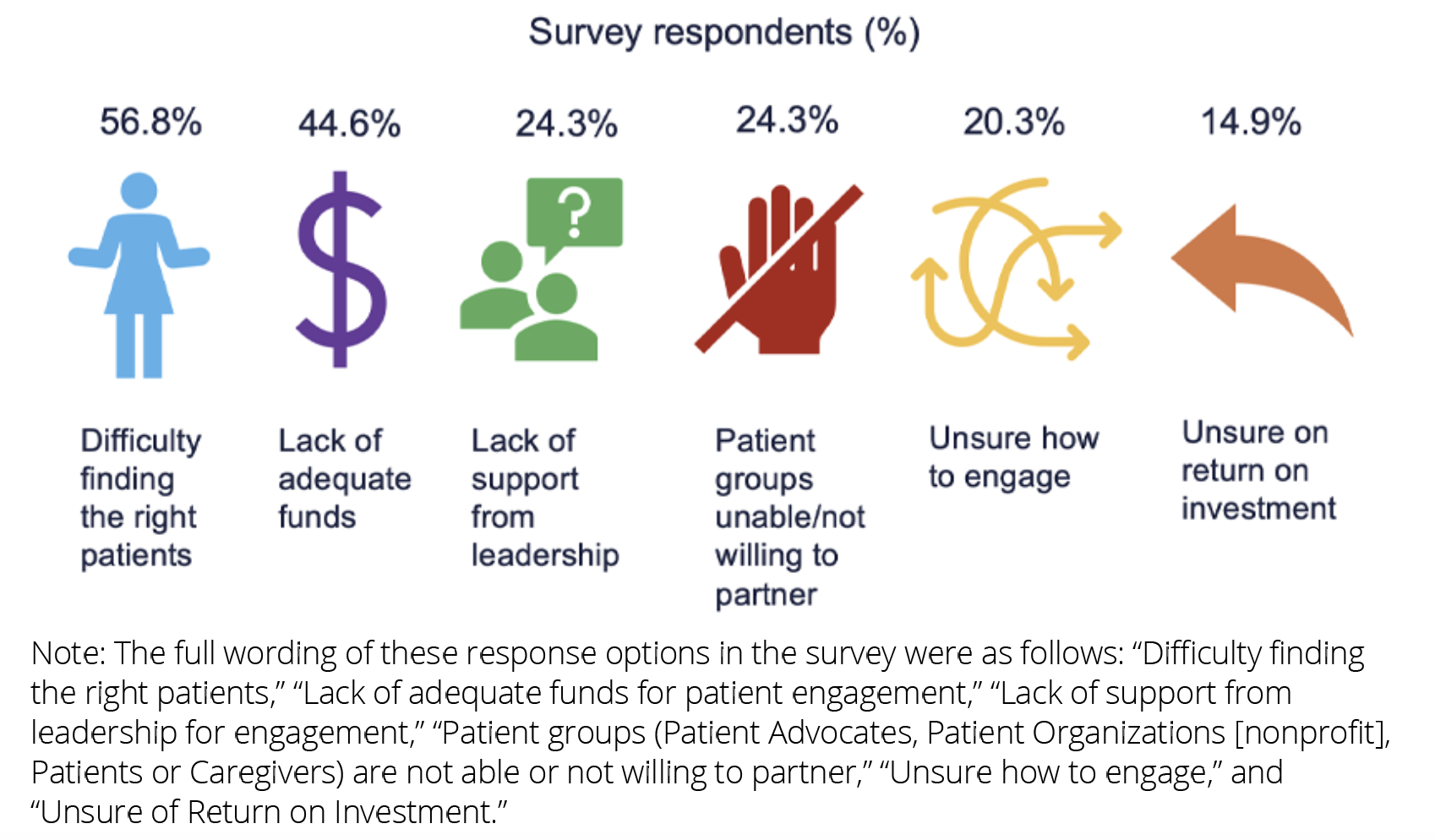

Respondents also identified prevalent barriers encountered when engaging patients in research endeavors. These results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Barriers encountered when engaging patients (n=74); respondents could select multiple responses

Experiences with assessing engagement quality

The survey highlighted the prevalent use of principles or guidance to inform engagement activities with patients, with 77.2% (n=57 responding to this question) utilizing such frameworks. Commonly reported principles or guidance included the US Food and Drug Administration’s Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance documents (43.9% of the n=41 responding to this question),7 the Patient Focused Medicines Development Patient Engagement Quality Guidance and the UK Standards for Public Involvement (both 22.0%),8,9 and the PCORI engagement rubric (19.5%).10

Frequently reported engagement methods were surveys (67.9% of the n=53 responding to this question), interviews (66.0%), focus groups (54.7%), patients on advisory panels/committees/work groups (50.9%), and patient consultants/advisors (41.5%). Virtual engagement was selected by the majority of respondents (92.5%) given multiple selection options.

Furthermore, the survey explored the evaluation and assessment of the quality of patient-engagement activities. Just under half of respondents (45.3% of the n=53 responding to this question) reported conducting evaluations, with the most frequently reported methods including participant interviews and focus groups (42.3%), formal internal protocols (34.6%), and the use of publicly available resources, questionnaires, or tools (26.9%). These findings provide valuable insights into the diverse approaches and practices surrounding patient engagement in research activities.

Of the 24 respondents answering the question, 16 (66.7%) reported that they asked patient research partners to assess the quality of their personal engagement experience as part of evaluation. The reported methods were “Participant interviews and focus groups” (56.2% of the n=16 responding to this question), “Formal, internal protocol in place” (25.0%), and “Use publicly available resources/questionnaires/tools” (18.8%). The remaining respondents stated that they did not do this.

Survey respondents (n=93) identified the top 3 attributes of good-quality patient engagement activities, with “Trust” ranking highest at 57.0%, followed closely by “Transparency” at 53.8%, and “Representativeness/diversity” at 48.4%.

Regarding the long-term outcomes of good-quality patient engagement in research, respondents (n=93) emphasized “Findings that change patient health” as their top choice at 52.7%. This was followed by “Better quality studies” at 23.7%, and “Increased patient trust in science” at 16.1%. These insights provide valuable perspectives on the perceived effectiveness and impact of patient engagement in research endeavors.

Insights and future directions

The survey results indicate there are areas that can be improved with regard to patient-engagement activities and the evaluation of the quality of those activities. Despite the majority of respondents considering their research as patient-centered, it is essential to address existing misconceptions and promote authentic patient-centered research. Specifically, there appears to be a lack of understanding regarding the definition and fundamental role of patient engagement in patient-centered or patient-focused research.

In particular, it is important for the HEOR community to recognize the distinction between patients as participants in studies and patients as active partners in development and design. Activities such as collecting patient experience, preference, or opinion data through qualitative methods such as focus groups, interviews, or preference elicitation methods are patient participation in research and not authentic patient engagement in research. This distinction appears to be unclear to many survey participants, highlighting the need for educational initiatives among the HEOR community. In addition, the finding that representativeness and diversity are among the most crucial aspects of engagement aligns with community efforts.4 However, the fundamental characteristic of patient-centered research—which involves including patients as partners throughout all stages of research—received only 57.3% of the votes.

"There appears to be a lack of understanding regarding the definition and fundamental role of patient engagement in patient-centered or patient-focused research."

In addition, patient organizations and individual patients currently play a crucial role in facilitating patient-centered research. Active participation of other key stakeholders should be promoted. Addressing the difficulties of finding representative patients with lived experience and securing sufficient funding are vital to advancing patient-centered research. Many participants cited funding as an important barrier, highlighting the need for better understanding of the value of patient engagement. This understanding can help the HEOR community appreciate the necessity of investing in patient engagement and the broader benefits it can bring to patient-centered research. This also relates to another survey finding regarding representativeness and diversity; adequate funding is an important aspect of reaching patients for engagement, particularly those who may be historically underrepresented in research.

The assessment of patient-engagement quality also appears to be an area needing greater attention. Awareness about the need for assessment, existing assessment tools, and needed research to enhance what is available should be advanced. Greater awareness of existing tools7,8,9,10 can support their uptake in practice and help us to understand how they can be further improved and built upon.

"It is important for the HEOR community to recognize the distinction between patients as participants in studies and patients as active partners in development and design."

Our hypothesis was that these 3 SIGs would naturally attract individuals who are more knowledgeable about the topic; thus, starting with these SIG members would provide a valuable baseline. We acknowledge that the results may not be generalizable to the entire ISPOR membership or the broader HEOR community.

The low response rate to certain questions, particularly those related to principles or guidance informing patient engagement and the assessment of its quality, suggests that a proportion of survey respondents may not be aware of available resources or standard practice and/or lack hands-on experience with patient engagement, making them unable or unwilling to answer these questions. Despite our inability to pinpoint an accurate reason, this candid depiction highlights the need for further efforts to engage and educate stakeholders on these topics. Such endeavors could pave the way for more informed and comprehensive responses in future surveys.

"Addressing the difficulties of finding representative patients with lived experience and securing sufficient funding are vital to advancing patient-centered research."

Conclusion

This snapshot of the HEOR community’s views and experiences with patient engagement and patient-centered research provides valuable insights about the need for further efforts within the HEOR community to understand and enhance patient engagement practices. This can be achieved through education, effective communication, and community capacity building among all HEOR stakeholders.

References

- ISPOR publishes new top 10 HEOR trends report. ISPOR—The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research. https://www.ispor.org/heor-resources/news-top/news/2024/01/16/ispor-publishes-new-top-10-heor-trends-report. Published January 16, 2024. Accessed March 13, 2024.

- Harrington RL, Hanna ML, Oehrlein EM, et al. Defining patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: report of the ISPOR patient-centered special interest group. Value Health. 2020;23(6):677-688.

- Advancing the science of engagement PCORI funding announcement–cycle 2 2023. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). https://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/announcement/advancing-science-engagement-pcori-funding-announcement-cycle-2-2023. Accessed February 19, 2024.

- Foundational expectations for partnerships in research. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). https://www.pcori.org/engagement-research/engagement-resources/foundational-expectations. Accessed March 20, 2024.

- Madelung M, Johnson S, Phillips S, Rickwood S. The Patient Engagement Framework: a holistic approach to patient inclusion. IQVIA. https://www.iqvia.com/blogs/2022/10/the-patient-engagement-framework-a-holistic-approach-to-patient-inclusion. Published October 20, 2022. Accessed February 19, 2024.

- Patient-Centered Special Interest Group. ISPOR—The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research. https://www.ispor.org/member-groups/special-interest-groups/patient-centered. Accessed March 13, 2024.

- FDA patient-focused drug development guidance series for enhancing the incorporation of the patient’s voice in medical product development and regulatory decision making. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/fda-patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-series-enhancing-incorporation-patients-voice-medical. Updated February 14, 2024. Accessed March 8, 2024.

- Patient engagement quality guidance. Patient Focused Medicines Development. https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/peqg/patient-engagement-quality-guidance.pdf. Published May 15, 2018. Accessed March 8, 2024.

- UK standards for public involvement. National Institute for Health and Care Research. https://sites.google.com/nihr.ac.uk/pi-standards/home. Accessed March 8, 2024.

- Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA. The PCORI engagement rubric: promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):165-170.

Acknowledgements

This

article was developed as a collaborative effort of members of the ISPOR

Patient-Centered SIG. We thank the ISPOR members who submitted responses

to the survey.

None of the authors received financial support for their participation. All authors volunteered their time for the development of this article. The research was supported in part by ISPOR, which contributed 3 staff liaisons (Sahar Alam, Rachel Peoples, and Clarissa Cooblall) for this project.