Comparison of Depression Trends in the Japanese and US Populations Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Observational Study Using Real-World Data

Sven Demiya, MBA, PhD; Shujiro Takeno, MBA; Louis P. Watanabe, PhD; Wen Shi Lee, MBBS, PhD; Yuri Sakai, PhD; Todd D. Taylor, PhD; Seok-Won Kim, PhD, IQVIA Solutions Japan KK, Tokyo Japan

Introduction

Since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March of 2020,1 there have been thousands of mental health-related surveys and reviews reported globally. Despite the abundance of mental health research, studies based on the analysis of real-world databases on the prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) are lacking. Compared to surveys and reviews, analyses on real-world databases can efficiently and quickly provide broad insights from outcomes data. This study used claims data from the United States and Japan to investigate the prevalence counts of MDD, and incidence of newly treated MDD were evaluated and compared for both countries.

"Understanding disease trends during the pandemic in a time- and cost-efficient manner would have been far more difficult without the support of large-scale real-world databases. Real-world studies such as this one can estimate the impact of government measures on trends in diseases such as major depressive disorder."

Databases and Cohort Definitions

This retrospective, noninterventional cohort study used the Japan IQVIA claims database and the US IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus claims database to compare the prevalence counts of MDD and the incidence of newly treated MDD patients in both countries.

The IQVIA claims database consists of payer claims data from the health insurance union for Japanese workers that were used to represent the Japanese population, while the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus data, which captures fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims data from national and subnational health plans and self-insured employer groups, were used for the United States. All datasets were anonymized to protect patient privacy.

The study population consisted of patients with an MDD diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, ICD-10 codes: F32, F33) between October 2018 and September 2021. The pre-COVID-19 cohort (cohort 1) comprised patients who received their first antidepressive treatment between April 2019 and September 2019. The baseline demographic characteristics for the Japanese cohorts can be found in Table 1. The COVID-19 cohort (cohort 2), investigated following the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic by the WHO, comprised patients who received their first antidepressive treatment between April 2020 and September 2020. The study design can be found in Figure 1. All analyses were performed using the IQVIA Evidence 360 Software-as-a-Service Platform containing global real-world datasets from more than 1 billion anonymized patient records.

Table 1. Baseline demographics of cohorts 1 and 2

Figure 1: Study design.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Patients With MDD

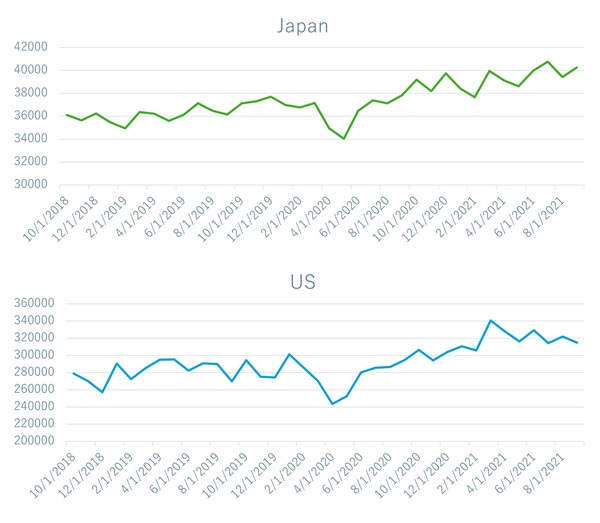

The prevalence counts remained steady until a significant drop in April 2020 in both countries. The prevalence counts increased gradually since then (Figure 2). Real-world data have been used to estimate the rate of transmission of the COVID-19, population-level vaccination status, and deaths in many countries.2,3 Understanding disease trends during the pandemic in a time- and cost-efficient manner would have been far more difficult without the support of large-scale real-world databases. The WHO declared the COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020. Since then, there was a significant drop in the diagnosis of MDD in Japan and the United States, likely due to a decrease in hospital visits due to social distancing measures and fears of COVID-19 transmission from hospital visits.4 MDD diagnoses increased steadily in the months that followed. Real-world studies such as this one can estimate the impact of government measures on trends in diseases such as MDD. Additionally, the results from this study are generally in agreement with a global systematic review from 2021 on the prevalence of depression and anxiety during COVID-19.5 Our study has thus shown the importance of using real-world data in the mental health field.

"The top comorbidity for patients with newly treated major depressive disorder in Japan was insomnia, while the top disorders for the United States were related to anxiety."

In Japan, the overall incidence of newly treated MDD patients increased from 2.0% to 2.3% from pre-COVID-19 (April 2019 to September 2019) to the time during COVID-19 (April 2020 to September 2020) (Table 2). The United States, on the other hand, saw no change in incidence during the same period (5.0% during both periods) (Table 2). Patients in neither country demonstrated a significant change in the duration of treatment. The discrepancy in overall incidence may result from a variety of factors such as cultural, economic, and policy in the patients between the 2 countries. Further investigation of the context surrounding these data may reveal why incidence increased in Japan but remained steady in the United States during the pandemic.

Figure 2: Prevalence counts of MDD in Japan and the United States during 2018-2021.

Table 2. Incidence of newly treated patients with MDD

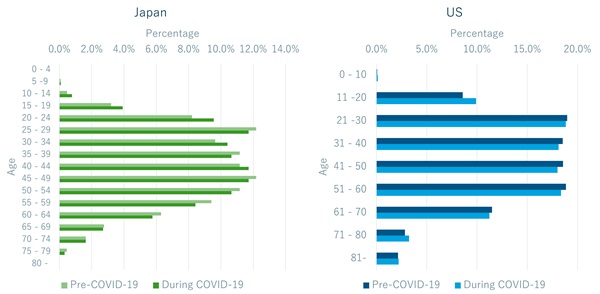

Before the pandemic, 3.7% of patients with newly treated MDD in Japan were below the age of 20 as opposed to 4.8% during the same period the following year (Figure 3). Interestingly, a similar increase was also observed in the United States with 8.6% and 9.9% of the patients being under 20 before and during the pandemic, respectively. Both countries implemented distance learning to various degrees during the pandemic, which may partially explain the increases in newly treated MDD. These trends are also seen in a survey study performed in the United Kingdom, indicating that similar trends may exist globally.6 There is ample research indicating the psychological burdens placed on children and adolescents from being barred from face-to-face interactions with their friends and peers during the pandemic.7,8 Future investigations of MDD for each country stratified by the timing of when children and adolescents returned to school may provide insights on the impact of distance learning on mental health.

Figure 3: Proportion, categorized by age, of newly treated MDD patients in Japan and the United States.

The top comorbidity for patients with newly treated MDD in Japan was insomnia, while the top disorders for the United States were related to anxiety (Figure 4). Other common comorbidities included respiratory diseases, lower back pain, and headache. These results are in line with other studies that indicate a rise in the mental health issues throughout the pandemic.9,10 Remote learning and work have been implemented in both countries to varying degrees and are expected to remain remote and to some extent continue even after the pandemic. Future database studies such as this one can be used to understand how these comorbidities may change over time as adjustments are made to the conditions brought about by events such as a pandemic.

Figure 4: Top 30 comorbidities of patients with newly treated MDD in Japan and the United States during COVID-19.

Limitations

Although database studies are a crucial component to gaining broad insights from real-world evidence studies, there are also several limitations. In this study, the number of elderly patients aged 60 and above is lower in the claims database than that according to actual Japanese and US demographics. Additionally, accurate denominators are required to determine prevalence, but are not available in the study data which may introduce bias during sample extraction. Finally, database studies in general do not necessarily reflect the overall population and the results may not be fully generalizable.

Conclusion

The prevalence count trends of MDD increased during COVID-19 in both Japan and the United States. However, the incidence of newly treated MDD was slightly increased during COVID-19 compared to pre-COVID-19 in Japan whereas there was no change in the United States. Among these, children and teenagers tended to have a higher proportion of newly treated MDD during the COVID-19 outbreak in both countries. Our study suggests the importance of using real-world data in the mental health field.

References

1. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157-160. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

2. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://covid19.who.int/

3. Blankenburg M, Fett A-K, Eisenring S, Haas G, Gay A. Patient characteristics and initiation of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease in routine clinical practice in the US: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrology. 2019;20(1):171. doi:10.1186/s12882-019-1348-4

4. Yoshida S, Okubo R, Katanoda K, Tabuchi T. Impact of state of emergency for coronavirus disease 2019 on hospital visits and disease exacerbation: the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey. Family Practice. 2022;39(5):883-890. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmac016

5. Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700-1712. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

6. Leach C, Finning K, Kerai K, Vizard T. Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: July to August 2021. Office for National Statistics. 2023. Published October 1, 2021. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusand depressioninadultsgreatbritain/ julytoaugust2021

7. Jones EAK, Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Mar 3 2021;18(5)doi:10.3390/ijerph18052470

8. Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie-Poon S, et al. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: a rapid systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7)doi:10.3390/ijerph18073432

9. Witcomb GL, White HJ, Haycraft E, Holley CE, Plateau CR, McLeod CJ. COVID-19 and coping: absence of previous mental health issues as a potential risk factor for poor wellbeing in females. Dialogues Health. Dec 2023;2:100113. doi:10.1016/j.dialog.2023.100113

10. Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. doi:10.12688/f1000research.24457.1