Understanding and Addressing the “Burden” of Asking Patients to Complete Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Clinical Trials: A Brief Summary

Matthew Reaney, PhD, CPsychol, CSci, IQVIA Patient-Centered Solutions, Reading, UK; Amelia Hursey, MSc, Parkinson’s Europe, Orpington, UK; Lindsay Hughes, PhD, IQVIA Patient-Experience Solutions, New York, USA; Jowita Marszewska, PhD, IQVIA Patient-Experience Solutions, Sylvania, Ohio, USA

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are questionnaires that explore how a patient perceives their medical condition, treatment, and/or trial experiences in a reliable, valid, and interpretable way. PROMs are becoming a critical component in the development and commercialization of new treatments and are now included in most pivotal clinical trials.1 Sometimes PROMs are the only way to understand the effects of treatments in trials, and to explore how treatment impacts symptom severity/frequency, day-to-day functional impairment, health-related quality of life, and treatment satisfaction. Many trials include multiple PROMs (a PROM battery) to measure different facets of how a patient is feeling or functioning.

The people designing clinical trials must balance the desire for insights with the potential burden on the patient and the research team.2 PROMs may seem burdensome to trial contributors unfamiliar with their value, so it’s important to note that insights from PROMs can be used for multiple purposes: to inform regulatory and payer decision-making, customize clinical care, establish expectations, and inform healthcare initiatives. Their value is thus significant across intervention development, and knowing this encourages researchers to collect as much PROM data as possible. However, if the PROM burden is too high, this will result in respondent fatigue, a lack of engagement, and a high level of missing data/unreliable responses undermining the utility of the data and increasing levels of participants’ dissatisfaction.

How many PROMs are too many?

No two PROMs are created equal. A clinical trial PROM battery can range from a few items, administered at occasional site visits, to more than 100 items administered weekly. While the latter seems burdensome, it may not always be. For example, Atkinson and colleagues administered 14 PRO questionnaires comprising 176 to 180 items to high-risk bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy and urinary diversion. Despite the large number of items, patients reported low response burden.3 There are plenty of other examples of patients willingly completing large PRO batteries in clinical trials.2 Burden should not, therefore, be defined by simply looking at the number of items in a PROM/battery and people designing clinical trials should not assume that less is better.4 While it is important to select PROMs that are not unnecessarily long and complex, having a unilateral focus on brevity may lead to missing the measurement of some important factors. It is perhaps relevant therefore to look beyond the number of items/PROMs when trying to define burden.

"Insights from PROMs can be used for multiple purposes: to inform regulatory and payer decision-making, customize clinical care, establish expectations, and inform healthcare initiatives."

So, what defines PROM burden in clinical trials?

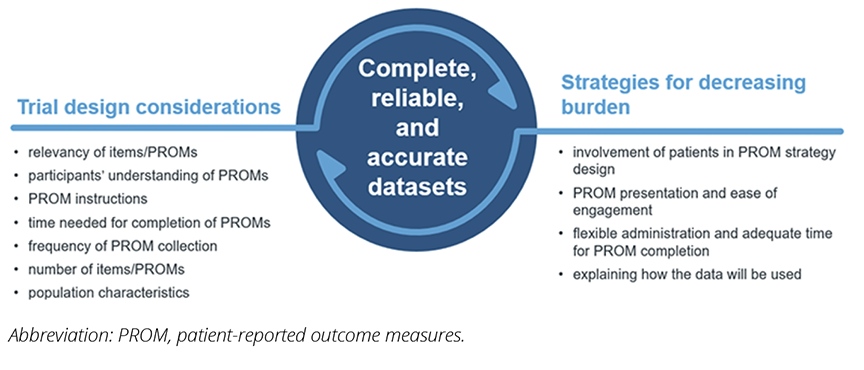

Multiple factors contribute to perceived PROM burden beyond the number of items/PROMs in a battery. These include difficulties in understanding or completing the PROMs, inadequate time for completion of the PROMs, and perceived irrelevance of the items/PROMs from a patients’ perspective.2-8

Difficulties in understanding or completing the PROMs

In general, a PROM has a brief set of instructions (telling the participant what aspect of their life or experience they are being asked about, what amount of time they should think about when answering the PROM [the recall period], etc, and a set of questions with response options. When patients do not understand the PROMs, engagement decreases. This leads to missing data or unreliable responses (eg, patients may choose a random option because they didn’t understand the question). A lack of understanding may be caused by unclear instructions or recall periods, and questions that are complex or unclear, therefore making it difficult to choose between answers. Although most modern PROM developers are constructing (and testing) simple questions to minimize confusion, some older PROMs (still widely used) are complex. When a PROM battery is used, different PROMs using varying recall periods, presentations, response scales, and repetitive requests of patients (choose a statement, select a number, cross a line, etc) can cause further confusion.

Inadequate time for completion of the PROMs

Sometimes in clinical trials there is not enough time allocated for patients to complete the PROMs or for staff to administer them. When the PROMs are aligned with a site visit but they don’t fit into the site staff’s workflow, missing data is common. Frequency of PROM administration is also relevant. Often, researchers reduce the number of timepoints to minimize burden, although the relationship between frequency of PROM collection and completion rates is weak. Rather, it seems that patients are willing to complete PROM data frequently (including multiple times per day) where they perceive it as an opportunity to tell their story and where they perceive a benefit to them personally.

Perceived irrelevance of the items/PROMs

Patients don’t want to answer questions that don’t seem relevant to their experiences or to help in understanding their condition or treatment(s). Perceived relevance of PROM items is an important indicator of burden. Indeed, Rolstad and colleagues said “if the questions are deemed relevant, patients are more likely to be motivated to respond” (p. 1107).4 They also highlighted the importance of avoiding overlapping items. For example, if a battery includes one PROM to measure clinical symptoms and another to measure generic quality of life, they may both have items that evaluate pain and activities of daily living. When studies involve multiple measures covering similar or identical concepts, or repetitive items, greater levels of burden are perceived.

Meaningfulness of PROMs is further reduced when patients do not receive the feedback of trial results after the study has ended.

Other contributors to PROM burden

Characteristics of the population enrolled in a trial should be considered in PROM inclusion. Level of literacy, physical fitness, health status, and technological aptitude and access influence perception of PROM burden. Social norms and cultural perspectives should further be considered when developing PROMs and administering them in diverse populations.

"Involving patients in the design of a PROM strategy offers an opportunity to identify and address any difficulties in understanding or completing the PROMs through iterative cognitive interviews."

How can we decrease PROM burden in clinical trials?

As described, burden in clinical trials is a multifaceted construct. Below we present some strategies that aim to minimize burden. We have intentionally selected solutions that we perceive as “low-hanging fruit”—that is, things that are already being done in some places (albeit not systematically), things that prior research has shown the benefit of, and things that are feasible within regulations of clinical trials. However, we recognize that there are also barriers to implementing these solutions, including trial budget, timeline, and adequate scientific, logistic, and resource considerations.

Involve patients in PROM strategy design

Trial participants want to share what they believe to be relevant and want this information to be used in decisions about whether treatment should be approved for use by other people like them.9,10 Involving patients in the design of a PROM strategy offers an opportunity to identify and address any difficulties in understanding or completing the PROMs through iterative cognitive interviews.1 These ensure appropriateness, acceptability, and clarity in the instructions, items, and response options, and test whether the proposed recall period is one that is sensical for the PROM concept being measured, and what people can accurately recall.2,8 Patient-centric design warrants collecting and presenting relevant data to inform decisions about treatment.2

Present PROMs in a way that is easy for people to engage with

How PROMs are visually presented can be modified to improve usability and ease of completion.1 Flexible modalities may also increase ease and convenience2 and improve inclusivity.

When administering PROMs via an electronic device (ePROMs), there are opportunities to present the study aim and a thank you message that is not easy to do on paper forms. This shows respect and gratitude, and it acknowledges a participant’s time commitment. Navigational guides and a progress indicator can also aid in following ePROM flow. Simple layout and consistent formatting help identify instructions and questions, and make it easier to respond. Notifications and reminders prompt participants to complete the required ePROMs at the right time, while using computer-adaptive testing or branching logic ensures only relevant PROMs/questions are displayed, reducing burden.2

Protecting adequate time for completion of the PROMs

Appropriate and dedicated time for patients to complete PROMs is part of study design, set-up, and training. For example, home (instead of site) administration of PROMs, use of a patient’s own smartphone (BYOD), or splitting PROMs administration may be considered to increase convenience and reduce time requirements.

Researchers may also need to convince clinic staff of the relevance and importance of PROMs where they have a role in administering them as well as ask them to help identify ways in which PROMs can be administered without interrupting normal workflow.9

Help people understand how the data will be used

Explaining to participants why PROM data are being collected, how it will be used, and informing them of results of the research10 maximizes engagement and investment by the participants in providing considered data.2,6,9 Recent initiatives aim to train researchers to communicate data to patients in an accessible way. For example, the UK Health Research Authority has launched the “Make it Public” strategy11 to encourage sharing of trusted information from health and social care research studies in public forums. As part of this, Parkinson’s UK developed a “Research Communications Toolkit” to assist researchers in continually communicating with study participants.12

Figure. Causes and remediation for PROM burden in clinical trials

"Explaining to participants why PROM data are being collected, how it will be used, and informing them of results of the research maximizes engagement and investment by the participants in providing considered data."

Conclusion

A poorly conceived PROM strategy may be considered burdensome for patients and produce unreliable data. A well-conceived PROM strategy, on the other hand, developed in conjunction with patients and with the aforementioned points in mind, is likely to produce valuable and informative data about how patients feel and function while using treatment in a clinical trial. A more detailed overview of techniques to address PROM burden is provided in Aiyegbusi et al.2

References

- Reaney M, ed. Using Patient Experience Data to Evaluate Medical Interventions. Generating, understanding and using patient experience data within and alongside clinical trials. IQVIA; 2023.

- Aiyegbusi OL, Cruz Rivera S, Roydhouse J, et al. Recommendations to address respondent burden associated with patient-reported outcome assessment. Nat Med. 2024;30(3):650-659.

- Atkinson TM, Schwartz CE, Goldstein L, et al. Perceptions of response burden associated with completion of patient-reported outcome assessments in oncology. Value Health. 2019;22(2):225-230.

- Rolstad S, Adler J, Rydén A. Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2011;14(8):1101-1108.

- Nguyen H, Butow P, Dhillon H, Sundaresan P. A review of the barriers to using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in routine cancer care. J Med Radiat Sci. 2020;68(2):186-195.

- Trautmann F, Hentschel L, Hornemann B, et al. Electronic real-time assessment of patient-reported outcomes in routine care—first findings and experiences from the implementation in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3047-3056.

- Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, et al. Durable usage of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice to monitor health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(12):3775-3783.

- Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Geller G, Carducci MA, Wu AW. Relevant content for a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for use in oncology clinical practice: putting doctors and patients on the same page. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):1045-1055.

- Serrano D, Cella D, Husereau D, et al. Administering selected subscales of patient-reported outcome questionnaires to reduce patient burden and increase relevance: a position statement on a modular approach. Qual Life Res. 2024;33(4):1075-1084.

- Continuous engagement - working with researchers to enable them to stay engaged with participants. Parkinson’s UK. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/. Accessed August 23, 2024.

- The Make it Public campaign group. NHS Health Research Authority. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/research-transparency/make-it-public-campaign-group/. Updated March 22, 2024. Accessed August 23, 2024.

- Stay connected with your participants. Parkinson’s UK. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/research/staying-connected-your-participants. Accessed August 23, 2024.