The Value of Technology to Reduce Barriers to Clinical Trial Diversity and Facilitate the Development of Patient-Centric Medicine

Nancy Cross, BSc,* Maddy Dawson, BSc, Lightning Health Ltd, London, England, UK

Introduction

Historically, participants of clinical trials have not been fully representative of the target patient population, with women, ethnic minorities (eg, Black, Asian, Hispanic), people with disabilities, and those under age 18 years and over age 75 years being consistently under-represented. This means that many patient subgroups, often those facing the greatest health challenges for whom clinical trials could provide life-saving therapies, are not being fairly considered during the clinical research process. This lack of diversity in clinical research can significantly impact our understanding of the effectiveness and safety of a treatment in the underrepresented subgroups and can result in a body of clinical knowledge that is not generalizable to the real-world patient population. Therefore, this issue can be considered both medical and moral.

However, increasing digitalization of clinical trials and advances in technology offer the opportunity to run more patient-centric trials and increase the representation of a wider patient population in clinical research.

An online research program utilizing the Lightning Insights platform was conducted with the aim to explore how advances in technology can increase patient-centricity in clinical trials, reduce the burden of trial participation, and increase access to a broader, more diverse pool of patients. Research was conducted with health technology assessment (HTA) and budget-holding stakeholders (herein termed payers) in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France. Telephone interviews were also conducted with specialist oncologists (key opinion leaders) in the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany. The research explored stakeholder perceptions of the barriers to clinical trial diversity, the key implications of a lack of trial diversity on both patients and society, and how technology can enable clinical trial cohorts to be more representative of real-world patient populations.

"This lack of diversity in clinical research can significantly impact our understanding of the effectiveness and safety of a treatment in the underrepresented subgroups."

Underrepresented patient cohorts in clinical trials

In discussion with key stakeholders across Europe and the United States, there was a clear consensus that patient cohorts involved in clinical research in oncology often lack diversity. Indeed, 91% of all respondents believed that clinical trials typically are not representative of all patient subpopulations, with only one payer (from France) considering clinical research carried out in public hospitals to be representative of all types of patient subpopulations.

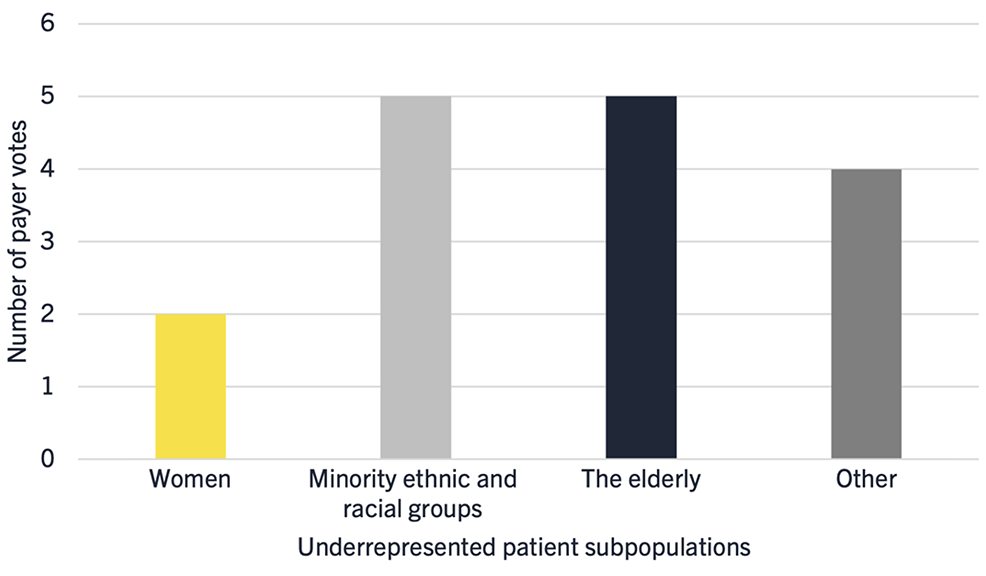

In particular, minority ethnic and racial groups and the elderly were highlighted as being underrepresented in clinical trials (Figure 1), which is consistent with the literature. For example, a recent analysis of oncology trials revealed that only 4% to 6% of participants in the United States are Black and 3% to 6% are Hispanic, despite representing 15% and 13% of cancer populations, respectively.1 Similarly, it has been reported that while individuals over the age of 70 years represent 50% of cancer patients, this cohort has historically represented just 13% of cancer trial participants.2

Figure 1: Payer perceptions of traditionally underrepresented patient subpopulations in clinical trials

Interestingly, key opinion leaders did not generally consider that women are an underrepresented group in oncology clinical trials, unless they were categorized as elderly, single parents, or those of a low social economic demographic. While the lack of representation of women in clinical trials has been well documented, this may be consistent with the positive trend of increasing representation of females in trials in the United States outlined in a recent report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.3 However, specifically in the field of oncology, this trend appears to have plateaued.

Barriers to clinical trial diversity

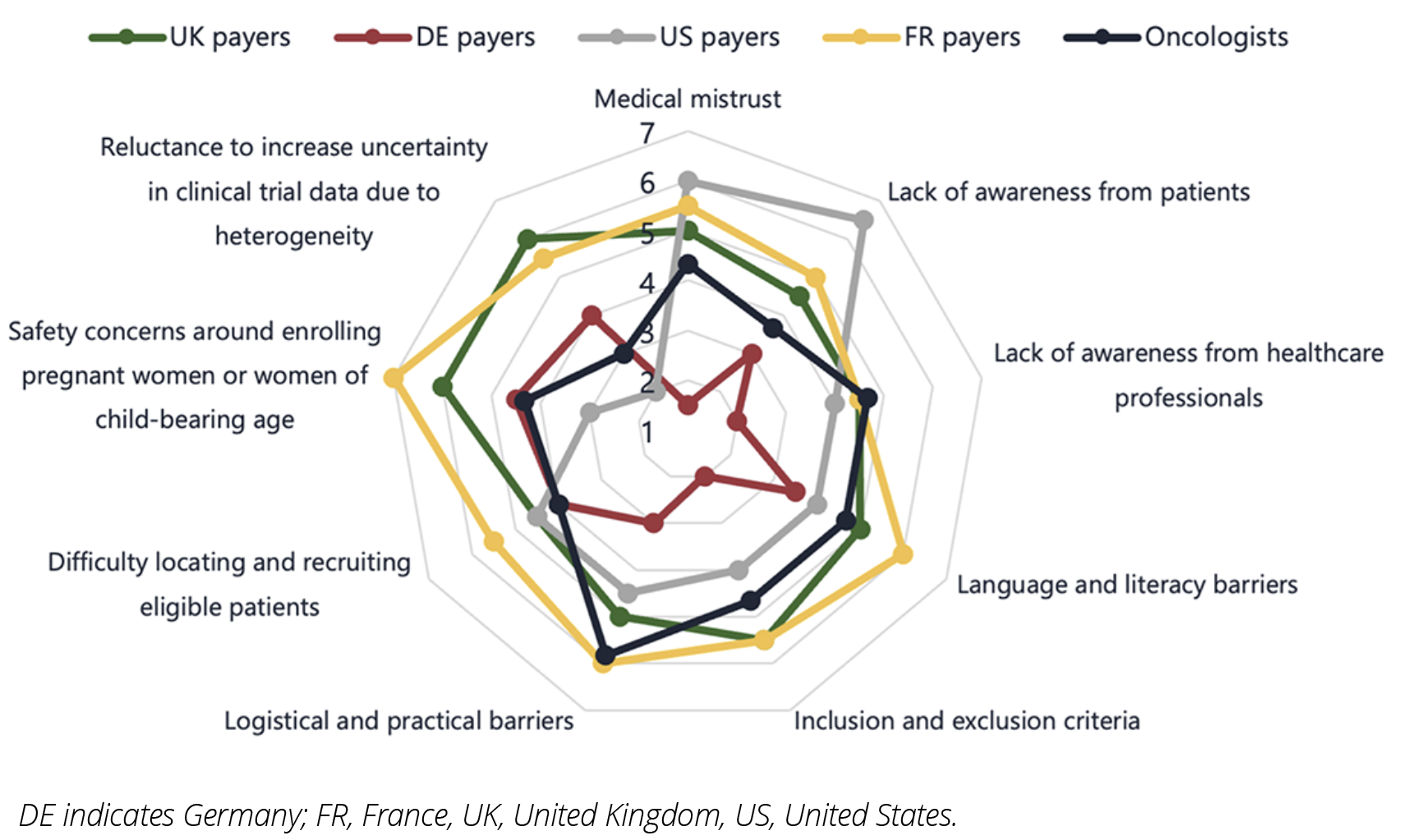

As illustrated in Figure 2, multiple factors are considered to be barriers to diversity in clinical trials. In particular, logistical and practical barriers to trial enrollment (such as access to transport, mobility, and support networks) were viewed as having a high influence on clinical trial diversity by the majority of payer and key opinion leader respondents.

The lack of inclusion of minority ethnic and racial groups is also interlinked with wider socioeconomic factors that contribute to individuals’ ability to take time off work, travel to clinical trial sites, and incur out of pocket costs. Language and communication barriers were considered a large determinant in the lack of ethnic diversity, influencing medical mistrust from patients and the willingness of principle investigators to recruit certain patients. Key opinion leaders also noted communication difficulties as a consideration when recruiting the elderly, alongside the increased likelihood of frailty, comorbidities, and lower performance status.

Figure 2: Stakeholder perceptions on barriers to diversity in clinical trials.

Other groups considered to be underrepresented included ”less fit” patients and those with comorbidities. As with elderly patients, there may be barriers to willingness to participate in clinical trials here, as well as potential bias from researchers to include “fit” patients who are more likely to respond favorably during the trial.

Implications of a lack of diversity in clinical trials

Lack of diversity in clinical trials has a very real impact on how advances achieved through clinical research are translated to treating patients in the clinical setting. Respondents in the research noted that lack of diversity has implications on the generalizability of results to the real-world patient population and can lead to treatment gaps, unsafe dosing recommendations and reduced access to innovative treatments in underrepresented groups. Furthermore, it may cause medical mistrust in minority populations who are not represented in clinical trials, potentially having a knock-on effect on treatment compliance.

There is valuable discussion to be had around how randomized controlled trial (RCT) outcomes translate to real-world patient populations.3 Driven by advances in technology and catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the landscape for conducting clinical trials is evolving, with stakeholders potentially more receptive to consider alternative methodologies that increase patient centricity and accelerate patient access to innovative new medicines.4

"Lack of diversity in clinical trials has a very real impact on how advances achieved through clinical research are translated to treating patients in the clinical setting."

The role of technology in reducing barriers to clinical trial diversity

Technology has the potential to facilitate increased representation of all relevant patient subgroups in clinical trials in several ways, for example:

- Faster and more efficient identification, recruitment, and enrollment of patients

- Recruitment of patients across multiple global locations

- Increasing patient centricity and patient engagement within clinical trials to reduce patient dropout

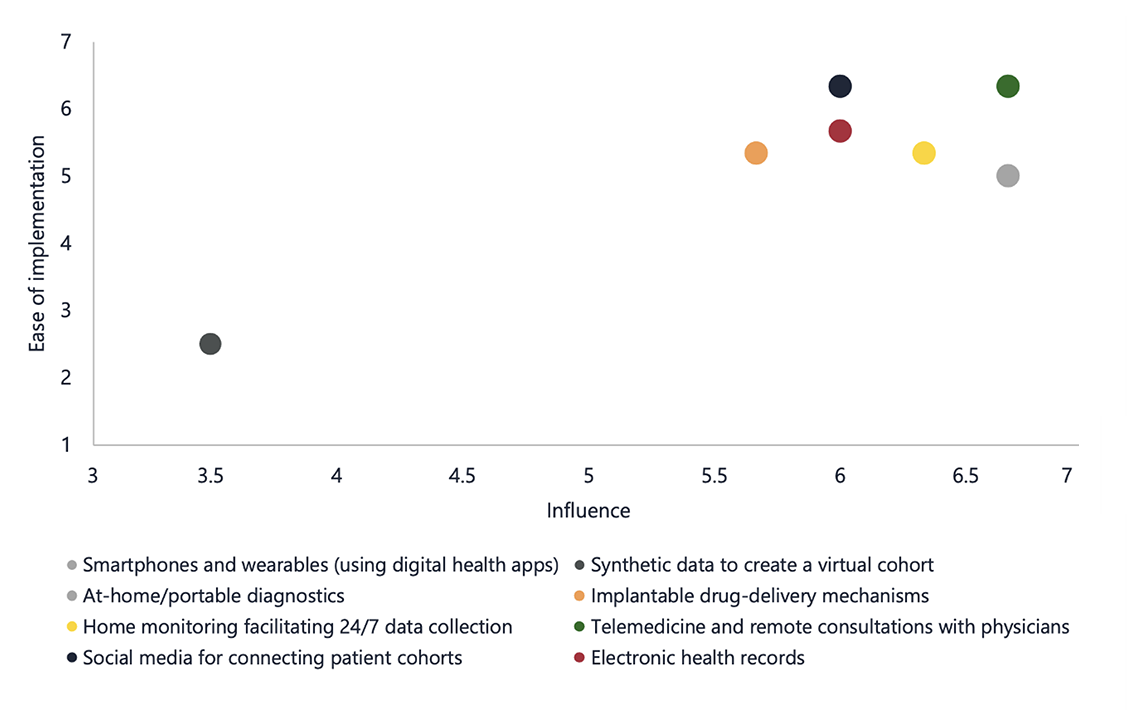

Telemedicine and access to remote consultations with physicians were considered by all stakeholders to be highly influential in their potential to improve trial diversity as well as being easy to implement (Figure 3). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in telemedicine, with a noted improvement in routine clinical practice management. This can be extrapolated to the clinical setting, where remote patient recruiting and consenting and video conference assessments can remove the need for participants to travel to the clinical trial site and report to the investigator, reducing time and costs and increasing convenience for the patient. At-home/portable diagnostics, smartphones, and wearables (using digital health apps) were rated as highly influential by key opinion leaders, but their implementation was considered more challenging, if, for example, traditionally underrepresented patient subpopulations (eg, the elderly) have limited access to these technologies and lack education on how they should be used.

Figure 3: Assessment of technologies according to their potential influence and ease of implementation for improving clinical trial diversity.

(Influence: 1 = low potential to influence the clinical development process and 7 = high potential to influence the clinical development process. Ease of implementation: 1 = difficult to implement and 7 = easy to implement)

Furthermore, virtual cohorts are digital nonidentical synthetic data records that preserve the statistical properties of the original data. They may be used for the simulation of clinical trials to augment datasets and detect effects in underrepresented groups in a study.5 However, stakeholders were generally unfamiliar with the use of synthetic data in clinical trials and lacked trust in the reliability of artificial intelligence algorithms to create virtual cohorts. Therefore, it is clear that no single solution exists to increase diversity in clinical trials, and education is a key component to be implemented alongside exciting, new technologies to ensure their full potential is realized.

"Advances in technology must be implemented appropriately within clinical trials to reduce barriers to trial involvement and increase representation."

Other strategies that can increase diversity in clinical trials

Outside of technology, other strategies could be implemented to increase representation in clinical trials. Regulatory requirements can have a role in encouraging sponsors to ensure increased representation in clinical trials. Currently, there are limited formal procedures to ensure that the demographics of the trial cohort are considered objectively when evaluating the data package in Europe or the United Kingdom. However, in the United States, draft guidance has been published to support pharmaceutical companies to ensure minority patients are represented in clinical trials, and some trials are now allowing extended periods of enrollment to certain minorities to meet this requirement.6 Furthermore, recent updates to the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review value assessment framework aim to promote equality in clinical trials through assessing the demographic diversity of participants in clinical trials.7 Across markets, however, regulations to enforce diversity, such as quotas, may be considered pragmatically challenging and potentially unethical.

Finally, stakeholders across countries emphasized the importance of engaging with patients to support increased diversity in clinical trials. For example, community outreach and social media programs aimed at educating patients about the importance and benefits of clinical trials, as well as increasing role models and representation of underrepresented groups among clinical trial staff are considered key ways to increase patient’s willingness to participate in clinical trials.

This speaks to a general shift in the pharmaceutical industry to prioritize the patient and encourage patient involvement in every stage of clinical research, with massive potential to improve representation and real-world patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Insights generated through consultation with payer and clinical stakeholders in key global markets confirm the well-documented historical underrepresentation of certain patient subpopulations in clinical trials. This has implications on the generalizability of results to real-world populations, impacting clinical outcomes, access to equitable healthcare, and potentially exacerbating health disparities that exist within communities. Advances in technology must be implemented appropriately within clinical trials, alongside education programs, regulatory requirements, and sustained patient-engagement to reduce barriers to trial involvement and increase representation. This should be implemented through updating regulatory frameworks to include assessments of clinical trial diversity, offering hybrid participation options for site visits, and using communication and marketing tools that will resonate with diverse patient populations.

References

- Oyer RA, Hurley P, Boehmer L, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in cancer clinical trials: an American Society of Clinical Oncology and Association of Community Cancer Centers joint research statement. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(19):2163-2171. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00754

- Gross AS, Harry AC, Clifton CS, Della Pasqua O. Clinical trial diversity: an opportunity for improved insight into the determinants of variability in drug response. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(6):2700-2717. doi:10.1111/bcp.15242

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering, Medicine. In: Bibbins-Domingo K, Helman A, eds. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. The National Academies Press; 2022. doi:10.17226/26479

- Cross N, Kipentzoglou N, Whitehouse J. Modernising the clinical trial: a shift to decentralised trials driven by advances in technology and catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. Lightning Health. Accessed May, 15, 2024. https://www.lightning.health/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Modernising-the-clinical-trial-a-shift-to-decentralised-trials-driven-by-advances-in-technology-and-catalysed-by-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf

- Muniz-Terrera G, Mendelevitch O, Barnes R, Lesh MD. Virtual cohorts and synthetic data in dementia: an illustration of their potential to advance research. Front Artif Intell. 2021;17(4):613956. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.613956.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials. Draft Guidance for Industry; Availability. Published online April 2022. Accessed May, 15, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/diversity-plans-improve-enrollment-participants-underrepresented-racial-and-ethnic-populations

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Value Assessment Framework. Published online 2023. Accessed May, 15, 2024. https://icer.org/our-approach/methods-process/value-assessment-framework/

*Affiliation at the time this paper was drafted.