Futureproofing Healthcare Financing in Six Association of Southeast Asian Nations Countries (ASEAN-6)

Jennifer Gill, PhD; Danitza Chávez, MSc; Caitlin Main, MSc; Aurelio Miracolo, MSc; Panos Kanavos, PhD, Medical Technology Research Group, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, England, United Kingdom

Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for good health and well-being (SDG3) sets targets for various aspects of healthy living and healthcare systems.1 It proposes a world where healthcare is a human right, aiming for universal health coverage (UHC) for at least 80% of the population, regardless of socioeconomic status or geographic area, by 2030.

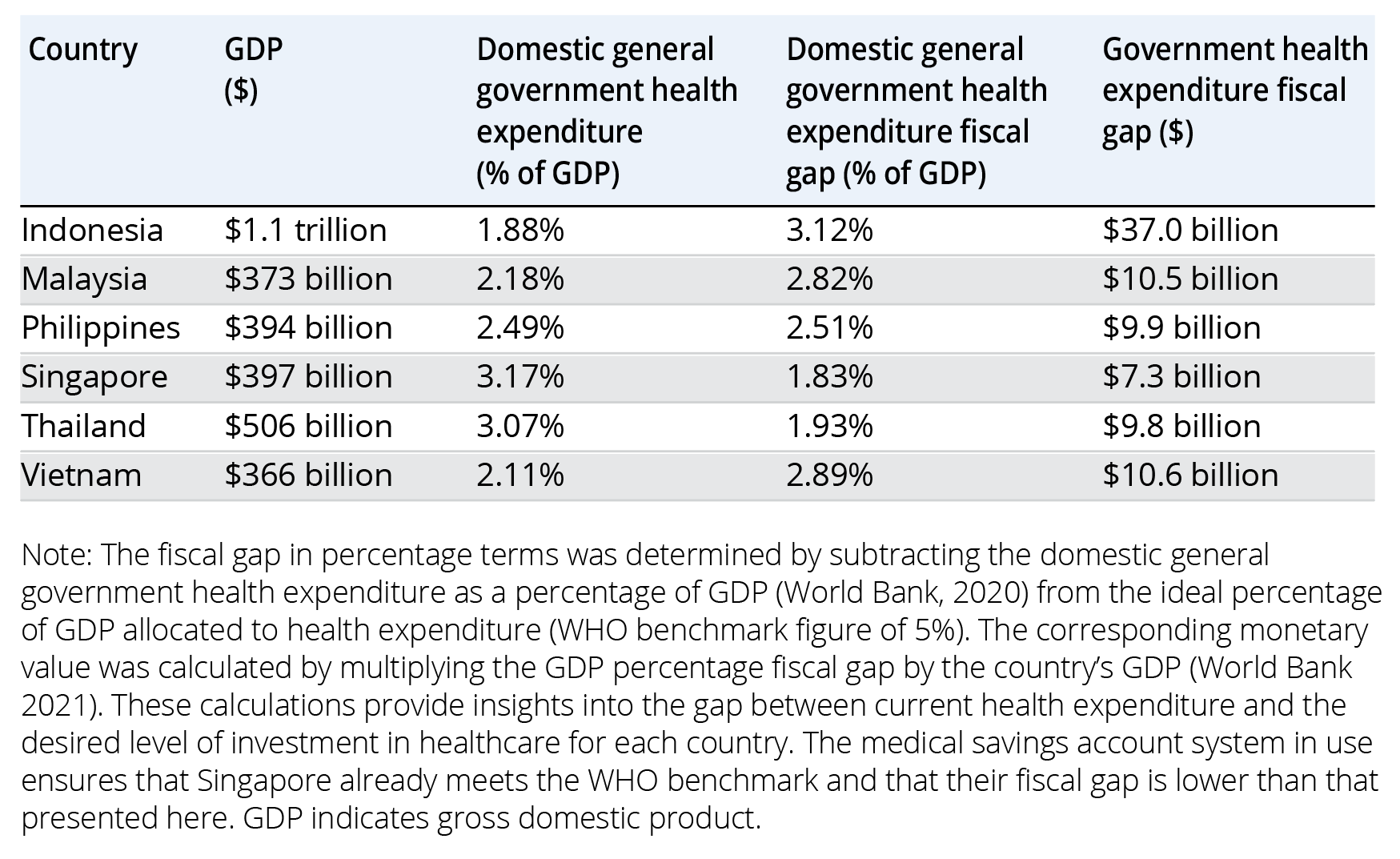

While certain countries in the Southeast Asia region have achieved several SDG3 targets, many are still on the road to achievement. They also face challenges funding healthcare and UHC with limited government fiscal space (the budgetary room allowing governments to provide resources to a public purpose without impacting financial sustainability), limited or absent social health insurance, and high out-of-pocket payments. In particular, there is a predicted annual fiscal gap of US$371 billion across low- and middle-income countries (Table 1), hampering UHC. To achieve UHC, countries need to overcome serious health financing challenges and establish sufficient and sustainable funds, protection from financial risks, and efficiency improvements in selecting and delivering available goods and services. In August 2023, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) health financing forum highlighted the urgency of creating sustainable funding, particularly in light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the threat of future pandemics, and the rising levels of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and comorbidities.2 We aimed to explore UHC-related challenges faced by 6 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries (ie, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam), as well as several health financing methods that may help achieve UHC and the broader SDG3 goals.

Table 1. Fiscal gap of government expenditure on healthcare in the countries of interest

Research methodology

Our investigation included mixed methodologies, including a semistructured literature review and a web Delphi exercise (using the Welphi platform www.welphi.com). The Delphi was designed to gather insights from key stakeholders regarding critical healthcare and healthcare financing challenges in the target countries. The 3-round Delphi used an analytical framework consisting of (1) 35 healthcare-related challenges and (2) 25 statements pertaining to financial mechanisms for increasing fiscal space. The stakeholders (eg, healthcare experts, members of the pharmaceutical industry, researchers and academics, health economists, and decision makers) from each of the target countries were asked to comment on and propose new healthcare challenges and potential financial mechanisms (round 1) and then rate their level of agreement/disagreement with the factors in their country context using a Likert scale (rounds 2 and 3). A total of 45 stakeholders completed all 3 rounds. This methodology allowed us to identify challenges facing national healthcare systems and gauge local appetite and willingness for potential financing mechanisms and reform.

"To achieve UHC, countries need to overcome serious health financing challenges and establish sufficient and sustainable funds, protection from financial risks, and efficiency improvements in selecting and delivering available goods and services."

Key healthcare challenges in ASEAN-6

We analyzed healthcare-related challenges across 5 areas: (1) general and UHC-related challenges, (2) financing challenges, (3) implementation challenges, (4) supply-side challenges, and (5) demand-side challenges. Specific detail on country responses can be seen in the accompanying report3 but in general, shared difficulties were felt across the region, including issues such as aging populations and increasing levels of NCDs. These factors impact both healthcare financing and demand. Older individuals often require more costly and complex care due to a higher prevalence of NCDs and comorbities,4 while the shrinking taxable workforce means less money for healthcare services. Further challenges identified across the nations include access inequalities, reduced health literacy in patients and healthcare workers alike, high proportions of informal workers, limited effectiveness of information technology in the healthcare system, and raw material cost increases.

Effective management of these issues requires integrated health systems and a shift in focus from secondary to primary care, as suggested by the UN 2023 High-Level Meeting on UHC.5 The optimal approach for primary healthcare is a blended provider payment mechanism with capitation (ie, a healthcare plan that provides payment of a flat fee for each patient it covers) at the core, linking the population with services. The involvement of performance-based payments for specific activities can also be beneficial.6 Singapore is a leader here with a focus on preventive care and a shift to capitation-based payments.7 Countries should concentrate on achieving full population coverage with affordable packages of services centered on prevention and delivered via effective primary care services. While they should look to build additional primary care infrastructure and address human resource gaps, they should also invest in effectively adopting digitalization in the healthcare space. Importantly, these steps should not be limited to the Ministry of Health; UHC is not the responsibility of health ministers alone. Our environment, socioeconomic status, and genetic predisposition all play a role in health and, as such, healthcare should not be thought of as “in silo” but should be considered in an interlinking manner with other aspects related to the social determinants of health. Action is required across government and must involve ministers of finance, environment, labor, and education, among others.

"Healthcare should not be thought of as “in silo” but should be considered in an interlinking manner with other aspects related to the social determinants of health."

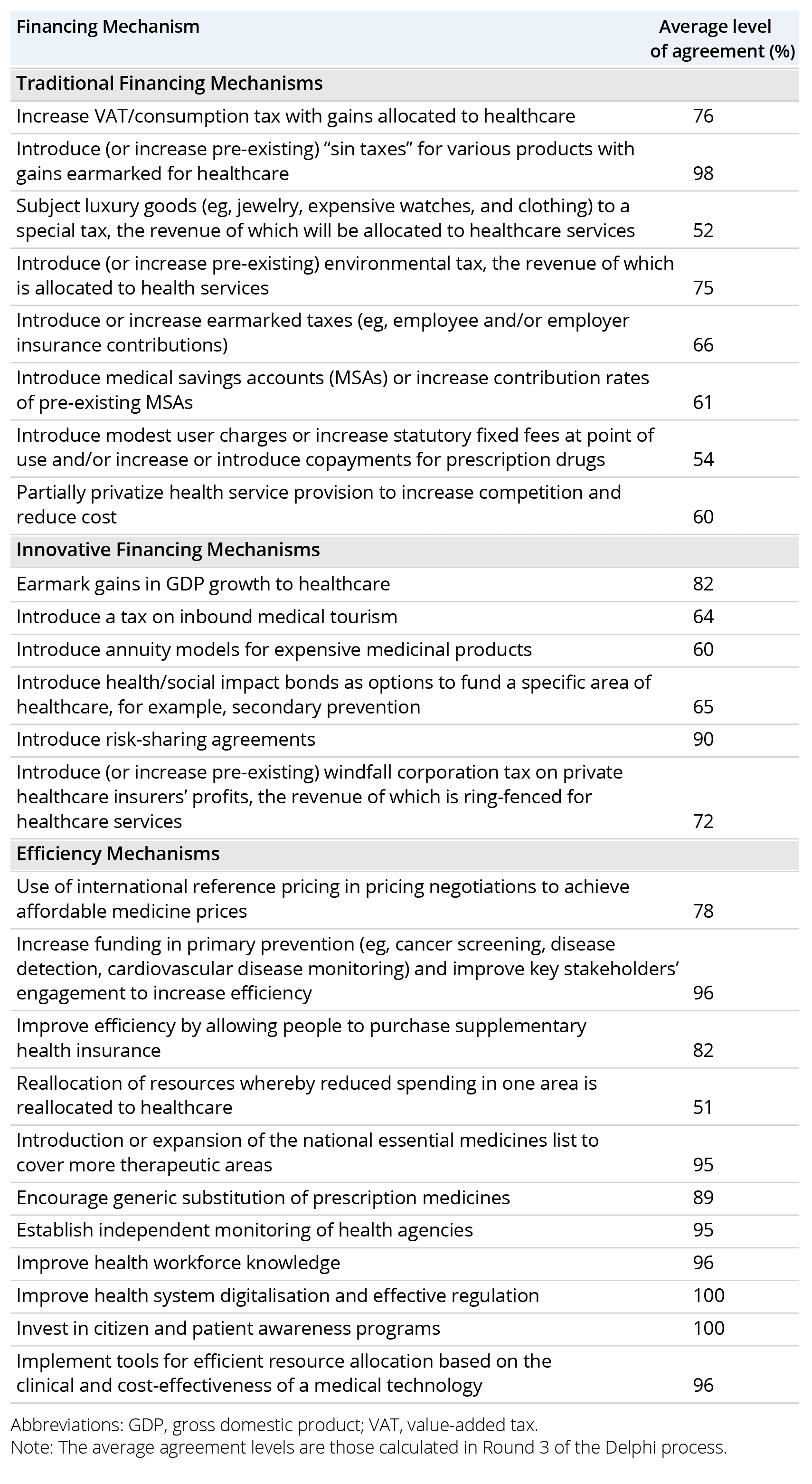

Increasing fiscal space for healthcare

Healthcare improvements are not possible without the generation of funds, and as countries progress toward UHC, fiscal space becomes a key factor in its success. It can be created by increasing healthcare expenditure efficiency and generating additional funds through various methods. Using the Delphi process, we assessed 45 stakeholders’ opinions on different mechanisms for increasing fiscal space. Again, specific results can be seen in the accompanying report.3 Unsurprisingly, efficiency in healthcare—the ability to deliver high-quality healthcare services while streamlining processes, minimizing waste, reducing costs, and optimizing resource allocation system8—proved popular among the stakeholders. There was an overarching level of agreement for each of the 10 efficiency mechanisms, suggesting they are an effective way to build fiscal space for healthcare (Table 2). Stakeholders also considered 8 “traditional” financing mechanisms, including taxation policies, health insurance, and social protection. “Sin taxes” proved popular, assuming revenue gains were earmarked for healthcare. Unsurprisingly, when you consider that if all countries increased excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverages by 50% worldwide, more than 50 million premature deaths could be averted over the next 50 years and more than USD $20 trillion of additional revenue could be generated.9 In contrast, partially privatizing the health system and introducing medical savings accounts received limited agreement despite the latter’s success in Singapore.10

Table 2. Financing mechanisms and average agreement levels across ASEAN-6 countries

Lastly, our analysis looked at 6 innovative financing models, including annuity models, risk-sharing agreements and health and social impact bonds. Risk-sharing agreements (ie, performance-based contracts using agreed-upon financial- or outcomes-based measures) were attractive to respondents from all countries. The use of annuity bonds (financial models that can provide a regular income stream in exchange for a lump sum or periodic payments) and social impact bonds (which leverage private capital to fund health, social, and development programs based on achieved outcomes) seemed less attractive to some, perhaps due to lack of familiarity. These mechanisms could play a valuable role in enhancing the fiscal space for healthcare in ASEAN countries. Furthermore, the focus on measurable outcomes ensures incentives for high performance, building accountability within the health sector. However, these rely on robust data collection facilities that require significant investment if not already in place. The private sector can also be engaged to raise UHC resources, both via foreign investment and blended financing. However, mechanisms for blended financing need to be strengthened, and legislation must be in place that allows for their development and implementation. Furthermore, local stakeholders should be fully engaged in a collaborative design approach to ensure the feasibility of any innovative financing mechanism in local contexts.

"A holistic approach from stakeholders within education, health, finance, and environment would ensure health improvements are sustainable, addressing health beyond the individual patient and incorporating the social determinants of health."

Conclusion and implications

The pursuit of UHC is fraught with significant financing and resource allocation challenges, alongside major demographic changes, including aging populations and the increasing prevalence of NCDs. While some countries have made considerable progress toward achieving the targets set out in SDG3, many are still grappling with limited fiscal space and high out-of-pocket payments. Our research highlights a need for a significant transformational change toward more integrated healthcare systems, focusing on prevention and primary care services.

Addressing the identified healthcare challenges requires a multifaceted approach, including stakeholders beyond the Ministry of Health. Efforts need to be made on the ground to improve health literacy as well as understanding and accessing available health system services. A holistic approach from stakeholders within education, health, finance, and environment would ensure health improvements are sustainable, addressing health beyond the individual patient and incorporating the social determinants of health.

Ultimately, achieving UHC in ASEAN-6 countries will depend on the ability of countries to mobilize sustainable funds, protect against financial risks, and implement efficient healthcare delivery systems. The engagement of the private sector, combined with innovative financing models and a collaborative design approach, will be crucial in generating fiscal space and ensuring access to effective healthcare for all citizens.

References

- The 17 goals. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Chair’s statement of the 13th APEC high-level meeting on health and the economy. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. https://www.apec.org/meeting-papers/sectoral-ministerial-meetings/health/chair-s-statement-of-the-13th-apec-high-level-meeting-on-health-and-the-economy. Published August 6, 2023. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Sustainable healthcare financing for SDG3 in ASEAN-6. The London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/business/consulting/assets/documents/Sustainable-Healthcare-Financing-for-SDG3-in-ASEAN-6-Final-Report.pdf. Published March 2024. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Tangcharoensathien V, TJ Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Thailand. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11.

- From commitment to action: action agenda on universal health coverage from the UHC movement. UHC 2030. https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/uhc2030/Documents/UN_HLM_2023/Action_Agenda_2023/UHC_Action_Agenda_short_2023.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Hanson K, Brikci N, Erlangga D, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on financing primary health care: putting people at the centre. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(5):e715-772.

- Shift to capitation enables better care for patients. Ministry of Health Singapore. https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/shift-to-capitation-enables-better-care-for-patients. Published April 27, 2023. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Zeng W, Yao Y, Barroy H, Cylus J, Li G. Improving fiscal space for health from the perspective of efficiency in low- and middle-income countries: what is the evidence? Glob Health. 2020;10(2):020421.

- Health taxes to save lives: employing effective excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverages. The Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health. https://www.bbhub.io/dotorg/sites/2/2019/04/Health-Taxes-to-Save-Lives.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed January 4, 2024.

- Wouters OJ, Cylus J, Yang W, Thomson S, McKee M. Medical savings accounts: assessing their impact on efficiency, equity and financial protection in health care. Health Econ Policy Law. 2016;11(3):321-335.