An Ecological Study of the Association Between Social Determinants of Health and the Incidence and Prevalence of Cancer at the County Level

Brenna L. Brady, PhD; Megan Richards, PhD; Liisa Palmer, PhD, Merative, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide, and estimates from the World Health Organization suggest that the incidence of cancer will continue to rise.1 Over the past few decades, major advancements in cancer treatment have improved survivorship and completely changed treatment paradigms across a variety of cancers.2-3 Further, increased understanding of the underlying causes of cancer, including genetic, environmental, and behavioral influences, have led to improved cancer prevention activities (such as human papillomavirus vaccination programs in cervical cancer or increased focus on regular screening in colorectal cancer).2 Although cancer prognosis continues to improve for many, globally 1 in 6 deaths are still attributed to cancer each year.

Given the inevitability of cancer within populations, positive outcomes are effectively defined by comparison (eg, lower incidence, longer survival, higher rates of remission). Although clinical trials have shown vast improvements in survivorship over the past decades, these benefits are not always realized in real-world populations, especially disadvantaged groups.2-3 Social determinants of health (SDoH), including behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic factors (such as accessibility of healthcare, which can be influenced by economic status, transportation, and health literacy), have been increasingly shown to influence both cancer risk and postdiagnosis outcomes.2-4 On the global stage, worse outcomes are commonly observed in poor and low-income countries where patients generally have access to fewer resources. Similar trends have also been reported in the United States with worse outcomes linked to disadvantaged social or economic status.1-4 Although SDoH have always influenced patient outcomes, the extent of their role in both the diagnosis and management of various conditions has only more recently become an area of focus.

"Although clinical trials have shown vast improvements in survivorship over the past decades, these benefits are not always realized in real-world populations, especially disadvantaged groups."

Research methodology

This analysis investigated the relationship between county-level incidence and prevalence of cancer and SDoH to evaluate disparities that may influence cancer risk. Annual county-level incidence (new cancer diagnoses) and prevalence (any cancer diagnosis) rates were calculated over the 2020 calendar year based on the presence of ICD-10 diagnosis codes in the claims record. The study sample was composed of patients in the Mertive™ MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Databases with medical and pharmacy eligibility for the entire year and 6 months prior. Patients with ≥1 cancer diagnoses in the last 6 months of 2019 were considered prevalent cases and excluded from the incidence analyses. Due to calculation of the incidence and prevalence of disease in the MarketScan Databases, the analysis reflects cancer risk among a sample of patients with employer-sponsored insurance. Unlike the broader US population, all individuals in this analysis had access to at least the federally mandated minimum levels of preventive care, via employer-sponsored commercial, Medicare Supplemental, or Medicare Advantage plans. This point does not remove all disparities in healthcare access, but it does address one notable barrier to care in the United States.2 County-level SDoH data were derived from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation County Health Rankings data and ascribed to the patient sample in the MarketScan Database based on county of residence.

This county-level assessment of the association between cancer rates and SDoH factors allows for a more socially focused analysis compared to individually linked SDoH data and may help to identify broader, persistent disparities in populations that specific individuals may not exhibit.3 For conditions like cancer, which are known to be influenced by environmental factors (eg, pollution), behavioral factors (eg, health literacy, willingness to seek care), and economic status, this ecological analysis provides a different perspective, potentially allowing for external, neighborhood influences to be investigated.

Results

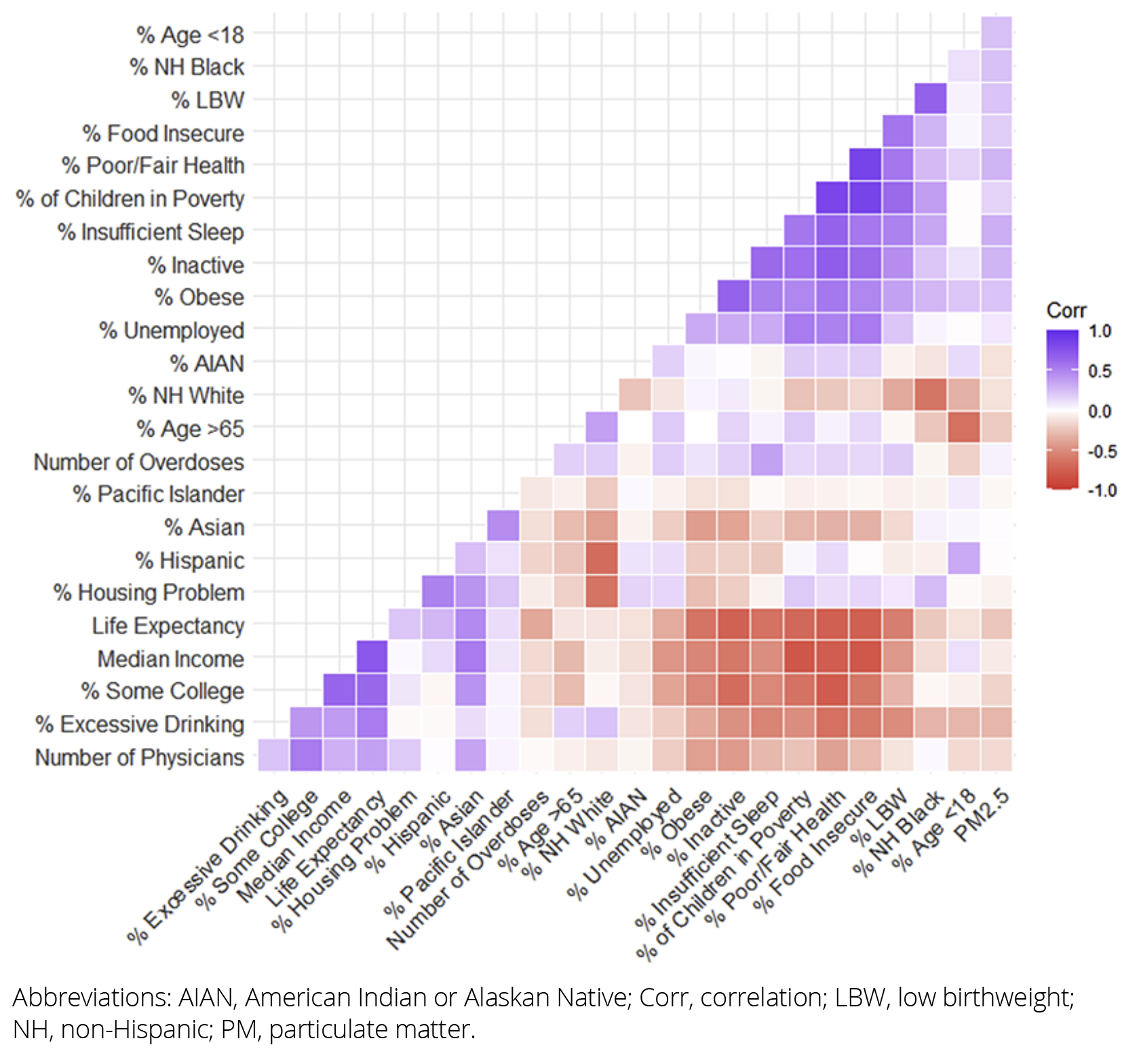

Analyses included 13.6 million patients residing in 2528 counties in the United States. Within the county-level SDoH data, strong correlations between specific variables were observed in the sample (Figure). For example, there were strong positive correlations between poor health, food insecurity, and child poverty, while there were strong negative correlations between poor health, median household income, and some college education. Multivariate models using Akaike information criteria stepwise linear regression identified associations between multiple demographic and SDoH variables and increased risk of cancer at the county level.

Figure. Correlation Between Social Determinants of Health Variables

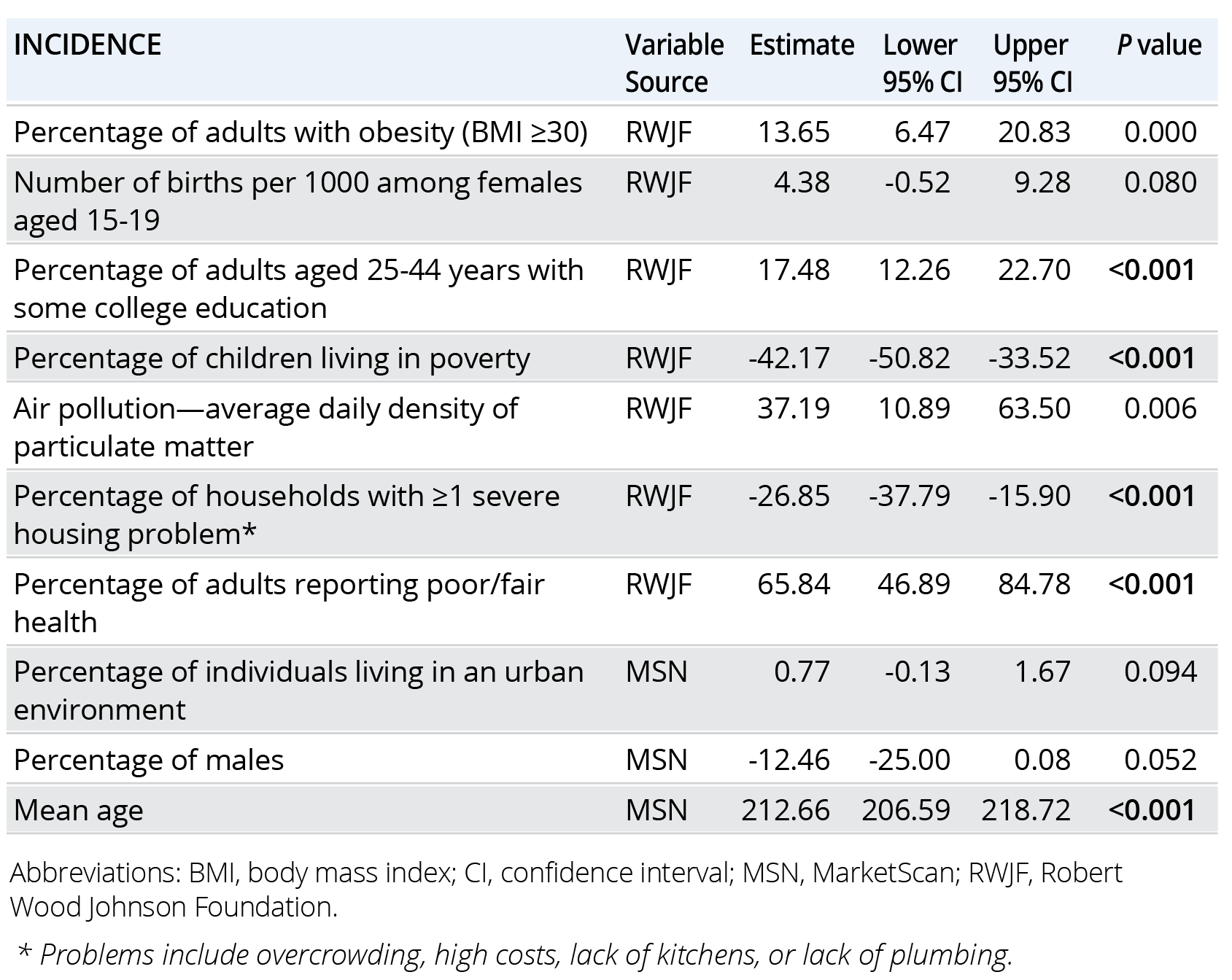

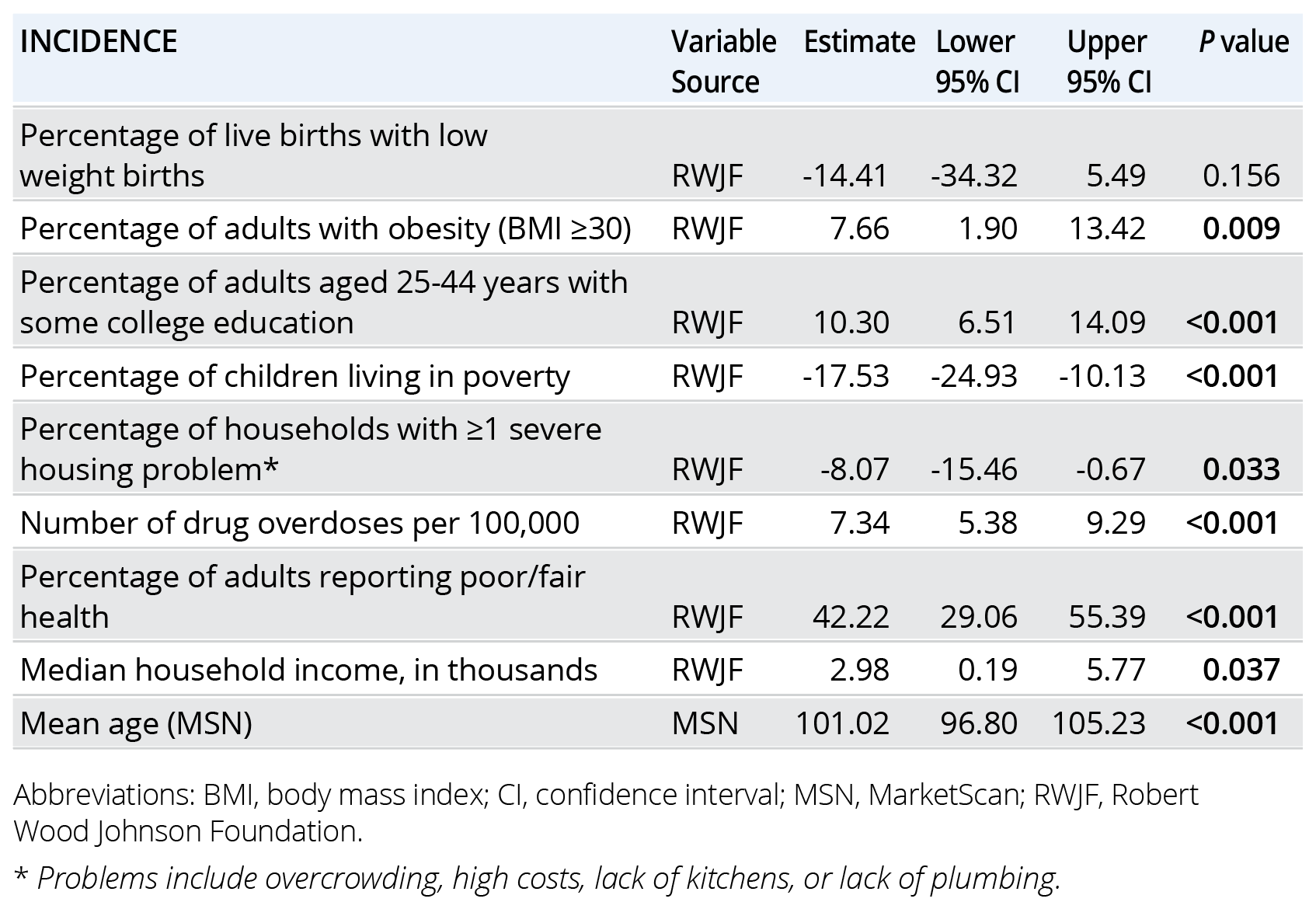

Increased cancer prevalence was significantly associated with (in order of strength) increased age, increased proportions of adults reporting poor to fair health (health status), lower rates of childhood poverty, worse air quality, lower rates of severe housing problems, increased proportions of adults aged 25 to 44 years with some college education, and higher rates of obesity in adults (Table 1). Increased incidence of cancer was associated with increased age, increased proportions of adults reporting poor to fair health (health status), lower rates of childhood poverty, increased proportions of adults aged 25 to 44 years with some college education, lower rates of severe housing problems, higher rates of obesity in adults, and higher rates of drug overdoses (Table 2).

Table 1. Prevalent Cancer: County-Level Risk Factors

Implications

This study investigated predictors of cancer risk at the county level by combining cancer incidence and prevalence rates calculated in the MarketScan Research Databases with SDoH data obtained from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Arguably, cancer rates were derived from the subset of the county that may have some of the fewest access barriers to healthcare—at least from an insurance perspective—as the population is composed of patients with employer-sponsored insurance. Thus, all individuals in the data are guaranteed to either be employed, previously employed (for Medicare), or have at least one employed family member. It’s important to note that the MarketScan-derived sample still includes a diverse cohort given that companies employ individuals in a variety of different roles that are associated with different income levels. SDoH factors from the broader community were then attributed to individuals, who may or may not embody the broader characteristics of their county. Although findings within this population may not generalize to patients with other types of insurance or the uninsured, the focus on patients with employer-sponsored insurance may also help to identify associations between SDoH variables and cancer risk that do not manifest in more heterogenous populations, potentially due to health insurance being one of the largest barriers to healthcare access.

Table 2. Incident Cancer: County-Level Risk Factors

Results from this study identify many of the same factors that have previously been associated with increased cancer risk, including overall health status, air pollution, and economic factors, highlighting the major contribution of geography (eg, neighborhood attributes) on patient health outcomes.2-4 However, both of our models also identified a series of less intuitive predictors—namely inverse relationships between cancer and childhood poverty (eg, higher poverty is associated with lower cancer rates) or housing problems and a positive relationship between higher education and cancer. Higher median income was also associated with higher cancer incidence. These findings likely point to a complex and interconnected set of relationships between SDoH and cancer risk. For instance, the overall SDoH data show an inverse relationship between childhood poverty and life expectancy, and although our models did not include life expectancy, older age was consistently the greatest risk factor for cancer; thus, there could be an interplay between age/life expectancy and childhood poverty leading to the relationships observed here. The same associations with age are not observed for housing problems or higher education in the SDoH data. In these cases, the positive association between cancer and college education (both models) and median household income (incidence model) could point to differences in healthcare access, even within this commercially insured sample, as patients who may have higher barriers to healthcare access—either due to health literacy, transportation, out-of-pocket costs, or locality of care providers—may see healthcare providers less frequently and would thus have fewer opportunities for a cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

Overall, this county-level analysis was able to identify previously reported relationships between cancer risk and SDoH factors, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach for population-level analyses. Further, assessment of cancer risk based on claims data derived from an employed population with employer-sponsored insurance provides a slightly different context than other studies, as employment has previously been described as one of the major influences on healthcare access in the United States.2 Additional research, potentially combining additional claims-based metrics such as county-level healthcare resource utilization trends, could help to further elucidate how SDoH influences healthcare engagement and patient outcomes in the United States.

References

- McDaniel JT, Nuhu K, Ruiz J, et al. Social determinants of cancer incidence and mortality around the world: an ecological study. Glob Health Promot. 2019;26(1):41-49.

- Minas TZ, Kiely M, Ajao A, et al. An overview of cancer health disparities: new approaches and insights and why they matter. Carcinogenesis. 2021;42(1):2-13.

- Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, et al. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:31-46.

- Bona K, Keating NL. Addressing social determinants of health: now is the time. JNCI Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(12):1561-1563.