Health Technology Assessment for COVID-19 Treatments and Vaccines: Will Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Serve Our Needs?

William Padula, PhD, MS, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Natalie Reid, PhD, MPH, MBA; Jonothan Tierce, CPhil, Monument Analytics, Baltimore, MD, USA

With the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) impacting nearly every society worldwide, now it is more important than ever to find practical solutions that differentiate COVID-19 patient care from other infectious diseases. This involves swift research and development of health technologies, including treatments and vaccines, to fight COVID-19. However, broad access to these solutions could be several months to years away, leaving the healthcare service industry (eg, hospital facilities and providers) as our current and best solution to help patients survive. This demand for healthcare services requires health economists to shift gears, to not only focus on health technology assessment (HTA), but also on value assessment of healthcare services.

"Despite healthcare services leading the United States in healthcare spending compared to testing and diagnostics, vaccines, and pharmaceutical treatments, traditional HTAs are not typically applied to healthcare services."

Fighting Back, but Paying the Price

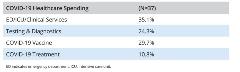

Attendees of the Virtual ISPOR 2020 workshop, “Understanding Intricacies of Value Assessment—Learning How to Conduct Economic Evaluation of Health Services and What Makes This Approach Different From Health Technology Assessment,” were asked, “What will the United States spend the most money on in the healthcare sector in 2020 to fight COVID-19 pandemic?” Thirty-five percent of respondents selected that the United States would spend the most on healthcare services in the fight against COVID-19, compared to health technologies for diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments in the next year (Table 1).1,2 Despite healthcare services leading the United States in healthcare spending compared to testing and diagnostics, vaccines, and pharmaceutical treatments, traditional HTAs are not typically applied to healthcare services. HTAs will only examine about 12% of the $3.5 trillion US healthcare budget. The United States needs to refocus on value assessment of other healthcare provisions, such as healthcare services.

Table 1. Twitter Poll: “What will the United States spend the most money on in the healthcare sector in 2020 to fight COVID-19 pandemic?”

Willingness to Raise the Threshold

During the same Virtual ISPOR 2020 workshop, another poll of attendees explored what the willingness-to-pay threshold should be for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Traditional willingness-to-pay thresholds have ranged from 1x to 3x the per-capita gross domestic product, falling within $50,000 to $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.3,4 Recent empirical work by Phelps indicates that the exact willingness-to-pay threshold for the US society is between $100,000 and $105,000 per QALY and Vanness et al estimates that it is approximately $104,000 per QALY.5,6 Relative to these values, should the threshold be higher to capture the exceptional value a COVID-19 treatment, vaccine, or cure would have on society? Or should it be a lower threshold to account for accessibility and affordability considerations? Or should it just remain the same as what good empiricism still suggests (ie, about $100,000 per QALY)?

The workshop attendees who were polled showed that there is no consensus on what the willingness-to-pay threshold should be. The results are a bimodal distribution of participants indicating a desired threshold of $50,000/QALY and others up to as high as $180,000/QALY (Table 2).7 The mixture of poll results regarding willingness-to-pay thresholds is interesting, perhaps highlighting mindsets across the spectrum amongst the workshop participants: (1) those selecting a lower willingness-to-pay threshold may worry about the connection between value assessment and price of technology; (2) those on the higher end of the willingness-to-pay threshold range communicate that innovation deserves to be rewarded in the macroeconomic implications; and (3) traditionalists choosing $100,000/QALY indicate that COVID-19 treatments should be no different than other technologies. Incidentally, a report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) evaluating the value and pricing of remdesivir to treat COVID-19 primarily cited a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY for their analyses, in addition to reporting $100,000 and $150,000 per QALY thresholds—we assume this since this was the bolded value that ICER reported in their “Base Case Model (assuming mortality benefit)”—putting them on the lower range of opinion while also including price points in their analysis at willingness-to-pay thresholds of $100,000/QALY and $150,000/QALY.8

Table 2. Twitter Poll: “US HTA’s willingness-to-pay has ranged from $50,000/QALY to $150,000/QALY, representing opportunity costs of next-best alternatives. COVID-19 is [trillions of dollars] in economic impacts and opportunity costs—we need to invest in a solution or many may die. What is the willingness-to-pay threshold for COVID-19 treatment or vaccine?”

Weighing the Cost of COVID-19

Regardless of the willingness-to-pay threshold that societies choose (and recognize that it is a choice) to value COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, or cures, the opportunity cost of doing nothing is too high. Dollars spent on the COVID-19 pandemic are not limited to the healthcare sector. The opportunity costs of these dollars span the entire economy—from businesses and employment, to education and housing, if not more. In a 2009 article, Becker cited that a pandemic could have a partial impact of $20 trillion on the US economy.9 His figure was adjusted for an “expected” risk of 1/100 of $20 trillion, leading to an expected impact of about $200 billion. However, now that it is 100% clear that COVID-19 is a global catastrophic event, the weighted impact of the pandemic on Becker’s figure should be 100/100 given zero uncertainty (ie, $20 trillion).

Becker’s rationale, based on the uncertainty of an imminent pandemic combined with the size of the economy that could be impacted, can be used to present another way of computing value. A technological solution for COVID-19 will offset a greater opportunity cost. The United States should be willing to draw 3 to 5 years of credit in order to maintain forward health and economic progress. Thus, the 3-year investment would be $60 trillion ($20 trillion Gross Domestic Product x 3 years). With 320 million Americans financing this investment, it would result in $187,500 per person ($60 trillion/320 million people). Thus, those who selected willingness-to-pay thresholds above $150,000 per QALY were not without cause, even if such logic had not yet been applied.

Looking at the Long-Term Impact

We have now seen the impact of reduced social distancing to reopen economies. It is arguable whether this juxtaposition between public health and the economy is fully valid. One could take the perspective that full economic activity requires nearly full health, and so when economic activity jeopardizes health, there is damage to both (hence, industrial pollution regulations, Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA] work safety regulations, etc). Whether we are spending money on healthcare services or moving towards vaccines or treatments that may be more efficient solutions, the debate will continue as to the fair market value of technological solutions to manage or eliminate the health risk and economic impact of COVID-19.

"The COVID-19 situation highlights the tensions between pricing, value, affordability, and ethics of healthcare services and technologies."

The effort and investment of finding a solution to COVID-19 is deserving on ethical and even moral grounds alone, since the alternative is continued loss of life in the United States and worldwide. While the success and timing of treatments and vaccine technologies coming through the pipeline is uncertain, it is certain that any technological solution for COVID-19 is a dominant strategy (ie, costs less and generates greater health benefits) compared to our only current options. Pouring unlimited dollars into ventilation and critical care for those that are sickest, keeping our economy shut down, and promoting self-isolation is not efficient. Isolation hurts the economy, education, and safe housing, not to mention the counteractive deterioration in physical and mental well-being caused by societal withdrawal and sedentariness from sheltering in place (Figure).

Figure. Impact diagram of health technologies on the COVID-19 global pandemic to repair burdens on the healthcare sector and the economy.

Final Thoughts

Between the many economic evaluations that have been published or are likely to come recommending different price points for COVID-19 technology, it is unclear whether cost-effectiveness analysis is the most appropriate solution to finding the price point. Any successful vaccine or effective treatment will dominate all current solutions—healthcare services and social distancing. A dominant strategy cannot provide a pathway to determine price, as most price points will still be cost saving. The COVID-19 situation highlights the tensions between pricing, value, affordability, and ethics of healthcare services and technologies. Perhaps other measures of economic evaluation with which ISPOR members are familiar, including budget impact, net health benefit, and net social benefit are the alternatives we need to consider first to guide decision makers towards high-value solutions at the right price.

Ultimately, traditional HTA-oriented cost-effectiveness analysis is best suited for comparing reasonably similar treatment choices within a reasonably narrow band of considerations within therapeutic areas. When applied to pandemic situations, the whole society and economy becomes part of the consideration. This is where the medical costs now include, and can even be dwarfed by, the costs of damage to the economy. Yet, the outcomes, not just years of life saved, but numbers of lives saved and impact on population growth, become unwieldy for traditional cost-effectiveness metrics. This is a very different context for valuing and pricing of technologies that can effectively address the underlying cause of the pandemic. The ISPOR community is well equipped with the methods to address the growing needs of value assessment related to COVID-19 and needs to leverage its diversity and expertise to develop a consensus for methodologies and recommendations on how to fairly value and price solutions for technology manufacturers that ensure affordability, accessibility, and innovation.

References

1 . @DrWmPadula. “What will the US spend the most $ on in the healthcare sector for in 2020 to fight #COVID19 pandemic?” May18, 2020. https://twitter.com/DrWmPadula/status/1262394043973148674.

2. Tierce JC, Padula WV, McQueen RB, Conti R. Understanding the Intricacies of Value Assessment: Learning How to Conduct Economic Evaluation of Health Services and What Makes This Approach Different From Health Technology Assessment. ISPOR Workshop; May 2020. https://www.ispor.org/docs/default-source/intl2020/econ-value-of-health-services-ispor-18may2020-final-for-archive.pdf?sfvrsn=cde3bb04_0.

3. Garber AM, Phelps CE. Economic foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16:1-31.

4. Neumann P, Cohen J, Weinstein M. Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-qaly threshold. http://www3.med.unipmn.it/intranet/papers/2014/NEJM/2014-08-28_nejm/nejmp1405158.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2021.

5. Phelps CE. A new method to determine the optimal willingness to pay in cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2019;22(7):785-791.

6. Vanness DJ, Lomas J, Ahn H. A health opportunity cost threshold for cost-effectiveness analysis in the United States. Annals Intern Med. 2020 Nov 3. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1392.

7. @DrWmPadula. “US #HTA Willingness-to-pay for has ranged from $50k/QALY-$150k/QALY, representing opportunity cost of next best alternatives. #COVID19 is $trillion in economic impact & opportunity cost clear: Invest in solution or many may die. What is WTP for #coronavirus treatment or vaccine?” May 13, 2020. https://twitter.com/DrWmPadula/status/1260651685057200128

8. Alternative Pricing Models for Remdesivir and Other Potential Treatments for COVID-19. May 1, 2020. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER-COVID_Initial_Abstract_05012020.pdf.

9. Becker B, Posner R. Some Economics of Flu Pandemics-Becker. https://www.becker-posner-blog.com/2009/05/some-economics-of-flu-pandemics-becker.html. Accessed January 22, 2021.

Explore Related HEOR by Topic