Deprioritized Children and Young People in Health Technology Assessment: Are Too Many Methodological Challenges Pushing Health Equity Down the Ladder in the Decision-Making Agenda?

Angeliki Kaproulia, MPharm, MSc, Donata Freigofaite, MS,* Andre Verhoek, MS, Cytel, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and Grammati Sarri, PhD, Cytel, London, England, UK

Introduction

Most health treatments used by children and young people (children and young people) are not explicitly authorized for their age group, illustrating the prevalent practice of off-label or off-license drug usage. Although children and young people account for 20% of the total European population,1 more than two-thirds of available medicinal products lack specific labeling for pediatric use and have not undergone the testing and validation necessary to ensure their safe and effective use in children.2 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stated that the absence of well-established pediatric use information in labeling poses serious threats to children and young people, as it may lead to inappropriate dosing and an increased risk for unsafe or ineffective treatments.3

The FDA and European Medicines Agency have provided clear guidance to tackle scientific and ethical issues related to the development of medicinal products for pediatric use.3,4 Although reimbursement decision makers seem to have acknowledged the unique challenges in evidence generation for this population, these issues cannot be properly addressed without modifying the standardized framework of clinical and cost-effectiveness assessments.

Only a handful of technology submissions for children and young people undergo formal assessment through the decision-making process. This can be the result of deprioritization in the health technology assessment (HTA) scoping phase or due to a high proportion of early development failure in treatments targeting children. For example, in a review of technology appraisals for children and young people from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) between 2013 and 2023, the annual percentage of HTA submissions ranged from 3% to 13%.5 In addition, the clinical and economic evidence included in HTA submissions is frequently suboptimal, lacking in both quality and quantity and failing to meet the minimum methodological standards commonly expected in adult indications.

Policy makers have taken steps to stimulate financial investment in pediatric drugs, aiming to eliminate barriers to undertaking clinical trials in children and young people by appointing pediatric specialists within federal regulatory and reimbursement bodies and funding research for children and young people.3,4 Several challenges have also been identified in HTA submissions for children and young people in terms of evidence generation, data quality, and extrapolations in economic models. The most widely discussed methodological topics are health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for children and young people and limited data follow-up.5

"Although children and young people account for 20% of the total European population, more than two-thirds of available medicinal products lack specific labeling for pediatric use and have not undergone the testing and validation necessary to ensure their safe and effective use in children."

Recent discussions have focused on how to expand value drivers in HTA decision making beyond clinical and economic considerations to include societal aspects; however, incorporating these value elements has been given much less contemplation in assessments of technologies for children and young people. For example, incorporating health equity is a core strategic initiative for adult diseases, but has been largely overlooked in the decision-making agenda for novel treatments for children and young people. This omission leaves children and young people more vulnerable to experiencing health disparities as adults even though resolving health disparities early in life will have lifelong implications for the entire population (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evidence Challenges in HTA Submissions for Children and Young People

"Incorporating health equity is a core strategic initiative for adult diseases, but has been largely overlooked in the decision-making agenda for novel treatments for children and young people."

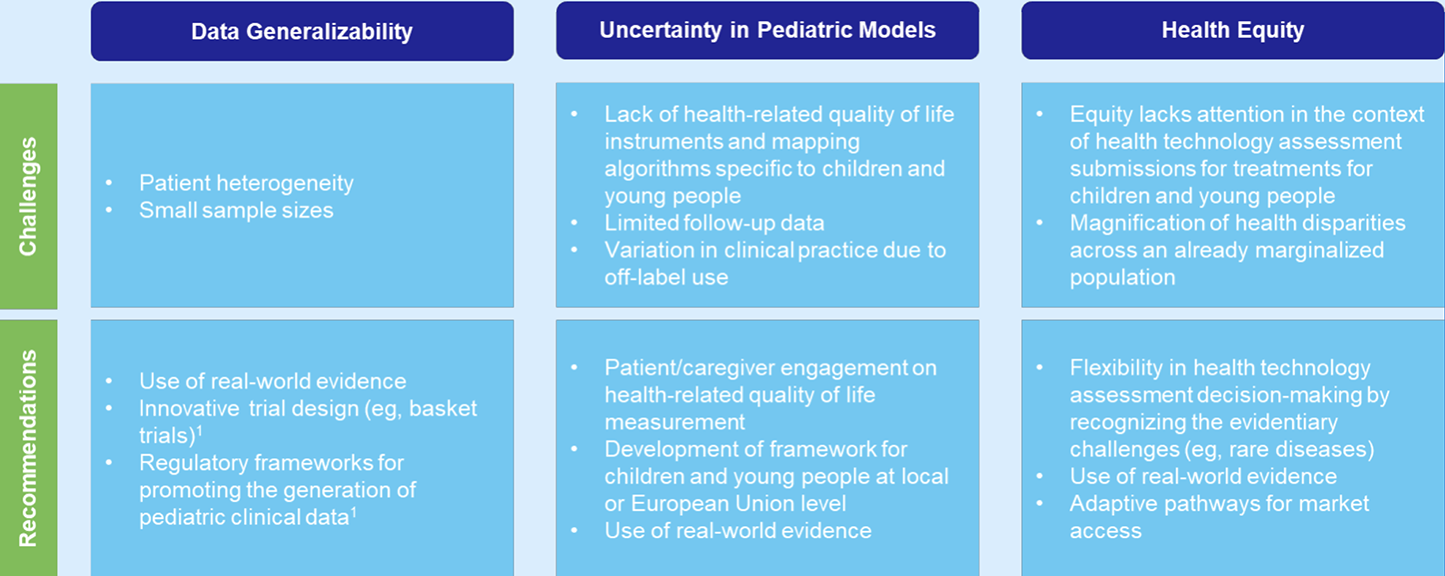

Data Generalizability

Data generalizability is a significant hurdle when building evidence packages from clinical trials or other sources for reimbursement decision making. Trial participants may not represent real-life patients who are more likely to receive newly available treatments. External validity of pediatric clinical trial data is more of a concern in submissions for treatments specifically intended for children and young people compared with adult trials, due to operational and ethical obstacles in trial recruitment. Industry has emphasized the difficulties in producing large and “high-quality” evidence in children that meets HTA standards, mainly related to pediatric disease characteristics (often in low-prevalence diseases/low numbers of children affected, need for dose-adjustment in a wider children and young people population) and high heterogeneity of pediatric patients in terms of anatomical, psychological, social, and cognitive development features.1 Researchers also struggle to recruit sample sizes large enough to statistically power studies to account for that heterogeneity or considered mixed-age clinical trials given the combination of societal, operational, and ethical barriers in pediatric clinical trial recruitment.

In a recent review of submissions to NICE for children and young people, committee critiques focused on increased uncertainty generated by small sample sizes in clinical trials and the extent these data can be generalizable to the local UK pediatric population. The large fluctuations in individual patient profiles (due to high trial heterogeneity) and the absence of confirmatory data on a treatment’s relative efficacy have been heavily criticized, increasing uncertainty in decision making. The interpretation of evidence was further complicated by the extent to which assumptions were made by borrowing adult data to resolve evidence gaps.

Uncertainty in Pediatric Models

The impact of methodological limitations in both generating reliable pediatric clinical data and confidently modeling the lifetime impact of health technologies on children and young people has been widely communicated.2 These limitations focus on the use of quality-adjusted life-year as a core metric given the inadequacies in the current methods to elicit preferences and attribute values per health state in children and young people as well as the lack of flexibility in economic model structures to address submission technical challenges in this population.

HRQoL among children and young people is difficult to measure due to scarcity of adequate/appropriate techniques or algorithms to map corresponding data in adults. Furthermore, children younger than 12 years of age may require caregivers to respond on their behalf,6 and proxy respondents might be influenced by their own perceptions.7

Model structure considerations such as altered time horizons, capability to account for treatment-related health states, and the need for long-term extrapolation of limited follow-up clinical data require stronger assumptions to resolve uncertainty. This is one of the largest areas of HTA critiques given the lack of trust in a treatment’s efficacy (health gain benefits) claims while the need for solid safety evidence remains critical.

The lack of reliable data to fit model inputs is also related to comparators in the decision problem. Off-label medications (often tested in adults) are used to treat various pediatric diseases given the absence of age-appropriate options. According to NICE, for instance, a manufacturer was unable to compare its technology to potentially relevant comparators because there were no pediatric studies that allowed for network meta-analysis.8

Health Equity

Health equity is achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being.9 For children and young people, this translates into increasing access to quality healthcare that accounts for their unique developmental and societal needs.

A range of political, socioeconomic, and contextual factors can affect health disparities. Despite increasing evidence about what impacts poor health, these health inequities have persisted, and in some cases, are getting worse. Many stakeholders have strongly advocated for the need to incorporate elements of health equity more widely in reimbursement assessments. Therefore, it is surprising that this is not a higher priority for pediatric HTA submissions given that childhood adversity can affect development and have a lifelong impact on health and well-being. Health equity is rarely discussed in HTA submissions for children and young people, seemingly falling far down a long list of methodological challenges involved in HTA submissions for this group. But this lack of attention to pediatric health disparities may further disadvantage already marginalized children, potentially resulting in worse health status and poor long-term health outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1. Challenges and recommendations associated with methodological and equity issues in CYP HTA submissions

"Health equity is rarely discussed in HTA submissions for children and young people."

Recommendations

Efforts are needed to ensure the integration of new medicines into routine clinical practice beyond the promotion of drug development and clinical trials (eg, innovative trial designs) for children and young people. Processes that have an impact on market authorizations and drug reimbursements are pivotal for guaranteeing equal access to new treatments for children and young people in daily practice.2

Real-world evidence can be of significant help to fill in evidence gaps and provide a long-term perspective, especially in trials with short follow-up and small sample sizes (eg, rare diseases). HTA bodies can assess the effectiveness and safety of an intervention across different pediatric populations using real-world evidence.

Flexibility in HTA decision making by recognizing a priori the evidentiary challenges is imperative to address health disparities effectively. These limitations are particularly pronounced in rare diseases, where issues such as the classification of disease severity across the children and young people population and, subsequently, the conduct of appropriate HTA evaluations have proven to be challenging.8,10

"HTA bodies have an opportunity to restore health equity by considering health disparities at the base of evidence."

Adaptive market access pathways can enhance early access to new technologies for patients and significantly contribute to tackling health inequalities. This discussion is particularly relevant for treatments targeting disease areas of high medical need among overlooked populations such as children and young people. It may involve regulatory approval in stages, incorporation of real-world evidence alongside clinical trial data, and engagement of patients and HTA bodies in discussions.11

Given the lifelong impact of treatments for children and young people on the health and well-being of individuals, HTA bodies have an opportunity to restore health equity by considering health disparities at the base of evidence. For example, international consensus on methods for measuring utility could promote the use of pediatric HRQoL instruments in clinical trials.12 In addition, eliciting social values through engagement with patients and caregivers would potentially fill in the gaps of HRQoL among children and young people.

Conclusions

While advances have been made in child-specific regulatory provisions for drug approval in the United States and European Union, reimbursement decision makers have not considered formulating changes in the methods to adjust evaluation criteria for technologies targeting children and young people, including prioritizing health equity in the evidence base.

References

- Mills N, Howsley P, Bartlett CM, Olubajo L, Dimitri P. Overcoming challenges to develop technology for child health. J Med Eng Technol. 2022;46(6):547-557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03091902.2022.2089254

- Moretti F, Ruiz F, Bonifazi F, Pizzo E, Kindblom JM, group tccHe. Health technology assessment of paediatric medicines: European landscape, challenges and opportunities inside the conect4children project. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(12):5052-5059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15190

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Pediatric Drug Development Under the Pediatric Research Equity Act and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act: Scientific Considerations Guidance for Industry. 2023.Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/168202/download

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on pharmaceutical development of medicines for paediatric use. 2013. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-pharmaceutical-development-medicines-paediatric-use_en.pdf

- Freigofaite D, Kaproulia A, Verhoek A, Sarri G. Health equity and the health technology assessment process: are children and young people being overlooked? a review of pediatric National Institute of Health and Care Excellence technology appraisals. Value Health. 2023;26(12):S366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2023.09.1924

- Prosser LA, Hammitt JK, Keren R. Measuring health preferences for use in cost-utility and cost-benefit analyses of interventions in children: theoretical and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(9):713-26. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200725090-00001

- Prosser LA, Ray GT, O’Brien M, Kleinman K, Santoli J, Lieu TA. Preferences and willingness to pay for health states prevented by pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):283-290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.2.283

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Secukinumab for treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children and young people (TA734). 2021. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta734

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health equity. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Risdiplam for treating spinal muscular atrophy (TA755). 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta755

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Adaptive pathways. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/research-development/adaptive-pathways

- Devlin N, Lovett R, Rowen D. Challenges in measuring and valuing children’s health-related quality of life. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2021;7(6). https://www.ispor.org/publications/journals/value-outcomes-spotlight/vos-archives/issue/view/finding-the-best-and-brightest-getting-a-leg-up-on-the-race-for-talent/challenges-in-measuring-and-valuing-children-s-health-related-quality-of-life

*Employed by Cytel at the time this manuscript was drafted.