Disability and Health State Utility Values: A Framework for Assessing Ableism and Equity

Dielle J. Lundberg, MPH, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, WA, USA; Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Over recent decades, scientists in the field of health economics and outcomes research have debated the measurement of health state utility values (HSUVs) for the calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) with little input from disabled people.* QALYs are calculated by multiplying HSUVs by the amount of time spent in a particular health state. HSUVs are scores that are typically reported on a scale from 0 to 1 to reflect the extent to which impairment reduces quality of life. Quality of life is defined by the World Health Organization as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”1 While some HSUVs are generated by asking disabled people about the impact of impairment on their quality of life and their preferences around impairment, many HSUVs are measured at least in part by asking nondisabled people to state their preferences for impairment by imagining its potential impact on their quality of life.2,3

Increasingly, disabled people have expressed concerns about the ethics of HSUV measurement methods that are based largely on the perspectives of nondisabled people.3 Despite the growing criticism of QALYs, little has been published about the ways in which these measurement methods meet the definition of ableism and how they may contribute to inequities in cost utility analysis and healthcare decision making. Ableism refers to beliefs, practices, and forms of systemic discrimination that privilege the nondisabled body and mind and frame them as ideal.4

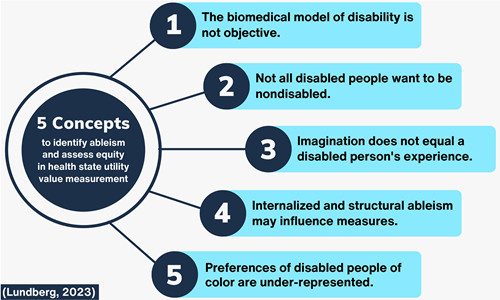

This article proposes a framework—“The Ableism and Equity in Measuring Health State Utility Values Framework”—to guide researchers in identifying ableism and assessing equity in their approaches to HSUV measurement. The framework includes 5 concepts to be considered, followed by companion questions that scientists can reflect on as they work to measure HSUVs and apply them in practice and policy settings. The framework is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Ableism and Equity in Measuring Health State Utility Values Framework

1. The Biomedical Model of Disability Is Not Objective.

Many of the concerns expressed by disabled people concerning HSUVs have their origins in the reliance of these methods on the biomedical model of disability.3 This model views disability as a deficiency or abnormality of the individual person that requires a cure to remedy it.5 Despite suggestions of its objectivity, the biomedical model is a subjective approach to understanding disability that reflects specific Western cultural values.6 An alternative model, the social model of disability, views disability as bodily difference that is disabling primarily because of physical, social, and structural barriers that limit activities and access to resources.5

HSUV measurement does not currently distinguish between quality-of-life impacts resulting from impairment and impacts resulting from physical and social barriers. If impacts relate to the latter, this has implications for healthcare decision making. It suggests that more resources should be devoted to community and structural-level interventions that eliminate barriers for disabled people rather than to individual-level interventions that seek to cure disability. This is not intended as an argument for large-scale disinvestments in medical interventions for disabled people but to question if prioritization of medical interventions is always appropriate to advance health equity.

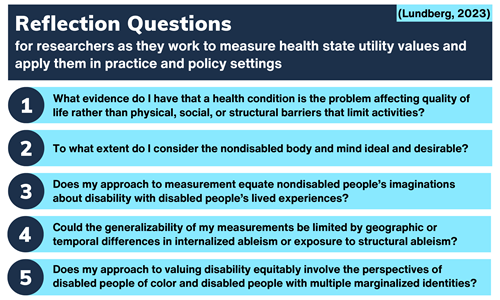

To explore this concept, researchers should critically ask: “What evidence do I have that a health condition is the problem affecting quality of life rather than physical, social, or structural barriers that limit activities?”

2. Not All Disabled People Want to Be Nondisabled.

An assumption embedded in HSUV measurement is that impairment reduces quality of life. Because of this, it is assumed that all disabled people would prefer a nondisabled life. This assumption is not well-supported by current literature. Studies have demonstrated that many disabled people would choose to be disabled if given the opportunity to be nondisabled.7,8 In practice, this assumption can bias researchers and cause them to adopt a deficit-based lens that leads them to overlook domains where disability may enhance quality of life. For example, a disabled person may develop relationships with other disabled people that improve their psychosocial health. While impairment does sometimes have negative impacts on quality of life and can warrant intervention, in cases where it does not, researchers may waste resources developing interventions that disabled people do not want. While it has been suggested that disabled people typically rate their quality of life higher than nondisabled people would expect them to, this finding actually varies across populations and domains.9,10

"Increasingly, disabled people have expressed concerns about the ethics of health state utility value measurement methods that are based largely on the perspectives of nondisabled people."

To explore this concept, researchers should critically ask: “To what extent do I consider the nondisabled body and mind ideal and desirable?”

3. Imagination Does Not Equal a Disabled Person’s Experience.

HSUVs are commonly generated using methods that involve asking the general population to imagine they have an impairment and provide their preferences for it. This is in opposition to methods that survey people living with impairment about their experiences and preferences. According to a systematic review, the majority of QALYs are calculated using HSUVs derived using data from the general population.2 This practice warrants scrutiny. Just as a study interviewing a majority group about the experiences of a minority group would be considered invalid, there is no evidence that nondisabled people can accurately report the experiences of disabled people. Some researchers have argued that surveying the general population includes disabled people, but this is flawed as well.3 A minority group’s perspectives are not going to be well-represented in a study where they are the minority. While some ethicists have argued that the general population’s preferences around health states should be prioritized in cost utility analysis because the public pays for healthcare, a major goal of contemporary healthcare is to reduce health inequities and allocate resources to populations with the most need. If this is the goal, it seems unreliable to assess the impact of an intervention on a minority group’s quality of life using a majority group’s imagination of the minority group’s experiences.

"While impairment does sometimes have negative impacts on quality of life and can warrant intervention, in cases where it does not, researchers may waste resources developing interventions that disabled people do not want."

To explore this concept, researchers should critically ask: “Does my approach to measurement equate nondisabled people’s imaginations about disability with disabled people’s lived experiences?”

4. Internalized and Structural Ableism May Influence Measures. When a disabled or nondisabled person is asked to provide their preferences around impairment, internalized ableism and exposure to structural ableism may influence their responses. In a community where inaccessibility and discrimination against disabled people are prevalent, respondents may be less likely to believe disabled people can have a high quality of life. They may also have implicit or explicit biases about disability. Since inaccessibility and discrimination vary by location and over time, generalizability of HSUV measurements may be limited. This is especially true if the population where valuation occurs is not representative of the population where the values are applied.

To explore this concept, researchers should critically ask: “Could the generalizability of my measurements be limited by geographic or temporal differences in internalized ableism or exposure to structural ableism?”

5. Preferences of Disabled People of Color Are Under-Represented.

The barriers that make impairment disabling have the greatest impact on disabled people who live at the intersection of structural ableism with structural racism and other systems of oppression.11-13 Due to these systems, in the United States for example, disability is more common among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native populations.14 However, studies that value health states often do not consider racialized identity in their sampling. If they do, they often have samples that over-represent White people. This raises concerns that disabled communities of color, who have unique experiences and values around disability, are not being adequately represented.

To explore this concept, researchers should critically ask: “Does my approach to valuing impairment and disability equitably involve the perspectives of disabled people of color and disabled people with multiple marginalized identities?”

Concluding Remarks

In summary, this article introduces a framework to assist researchers in identifying ableism and assessing equity in their approaches to measuring HSUVs. Reflection questions are also offered, which are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Companion Questions for the Ableism and Equity in Measuring

Health State Utility Values Framework

"Determining whose experiences and preferences are valued in quality-of-life measurement is an important consideration for increasing equity in healthcare decision making."

This article helps bridge the gap between disability justice advocates concerned about ableism in healthcare and health economics and outcomes researchers who believe cost-utility analysis is an important tool for healthcare decision making. This work is particularly relevant given congressional legislation in 2023 to prevent the use of QALYs in federal healthcare coverage and payment decisions in the United States. Regardless of the QALY’s future, the concepts and questions raised in this framework will remain relevant to the broader project of reducing ableism in quality-of-life measurement.

While the framework proposed here is most relevant to considering equity concerns in HSUV measurement for disabled people, some of the ideas may also be applicable to other populations.? Experiences and preferences around quality of life are likely to differ by gender, race and ethnicity, nationality, geographic location, and other dimensions of human diversity. Determining whose experiences and preferences are valued in quality-of-life measurement is an important consideration for increasing equity in healthcare decision making. New dialogue is needed around how the perspectives of marginalized and multiply marginalized people are included in quality-of-life measurement processes.

Ultimately, QALYs and HSUVs would be less of a concern for disabled people if disabled people were adequately represented in healthcare decision making.15 If disabled people are not at the table when measurement approaches are selected and when healthcare decision making occurs, choices can be made that are not in line with disabled people’s needs. This may cause harm and be counterproductive to advancing health equity. In this way, increased representation of disabled people in research and health policy is the ultimate structural solution to most of the issues raised in this article.

Funding/Support

This project was supported by grant number T32HS013853 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes:

a) I use identity-first language (ie, disabled person) instead of person-first language (ie, person with a disability) to emphasize disability as a social, cultural, and political identity in addition to an experience of living with impairment. While this intentional choice reflects my own language preferences as a disabled person and the preferences of many disabled people, there are diverse views about language within disabled communities.

b) The issues raised in this article are likely to also hold relevance for disability-adjacent populations (ie, those who are not disabled but are neurodivergent or chronically ill).

References

1. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL). World Health Organization. Published March 1, 2012. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-HSI-Rev.2012.03

2. Räsänen P, Roine E, Sintonen H, Semberg-Konttinen V, Ryynänen OP, Roine R. Use of quality-adjusted life years for the estimation of effectiveness of health care: A systematic literature review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(2):235-241. doi:10.1017/S0266462306051051

3. National Council on Disability. Quality-adjusted life years and the devaluation of life with disability part of the bioethics and disability series national council on disability. National Council on Disability. Published 2019. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Quality_Adjusted_Life_Report_508.pdf

4. Goodley D. Dis/ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2014.

5. Goering S. Rethinking disability: the social model of disability and chronic disease. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(2):134-138. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z

6. Valles S. Philosophy of Biomedicine. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Published 2020. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/biomedicine/

7. Hahn HD, Belt TL. Disability identity and attitudes toward cure in a sample of disabled activists. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(4):453-464. doi:10.1177/002214650404500407

8. Shaw SCK, McCowan S, Doherty M, Grosjean B, Kinnear M. The neurodiversity concept viewed through an autistic lens. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(8):654-655. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00247-9

9. Rowen D, Mulhern B, Banerjee S, et al. Comparison of general population, patient, and carer utility values for dementia health states. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):68-80. doi:10.1177/0272989X14557178

10. Ludwig K, Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Kreimeier S, Greiner W. To what extent do patient preferences differ from general population preferences? Value Health. 2021;24(9):1343-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2021.02.012

11. Annamma SA, Connor D, Ferri B. Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2013;16(1):1-31. doi:10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

12. Mingus M. Changing the Framework: Disability Justice. Leaving Evidence. Published February 12, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2023. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice/

13. Lewis TA. Working Definition of Ableism - January 2022 Update. Talila A. Lewis. Published January 1, 2022. Accessed February 18, 2023. https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/working-definition-of-ableism-january-2022-update

14. Courtney-Long EA, Romano SD, Carroll DD, Fox MH. Socioeconomic factors at the intersection of race and ethnicity influencing health risks for people with disabilities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(2):213-222. doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0220-5

15. Rotenberg S. Integral to inclusion: amplifying public health leaders with disabilities. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(8):e543. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00141-9