The Use of Item Banks in Rare Disease Clinical Trials: A Look at the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)

Julia Poritz, PhD, Leah Wiltshire, BPharm, Elizabeth Hubscher, PhD, Cytel, Waltham, MA, USA

Introduction

When designing clinical trials for a rare disease, an important consideration is that the outcomes are clinically relevant and interpretable.1 This consideration should be applied not only to clinical outcomes but also to patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQoL). However, there are challenges with PRO assessment in rare disease clinical trials.2

An ISPOR emerging good practices report was published in 2017 that specifically addressed PRO assessment in rare disease clinical trials.2 The report stated that the main challenges associated with PRO measure selection in rare disease research include limited availability of disease-specific PRO measures and substantial heterogeneity in symptoms between patients with a rare disease, thereby impacting the ability to measure outcomes across the entire spectrum of the disease.2 One solution that could address both challenges is to consider using item banks, such as the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), because they allow for the selection of the most appropriate items for patients.2

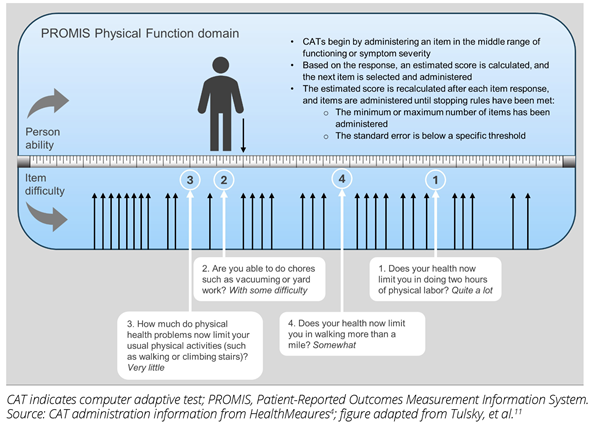

PROMIS measures can be administered in various formats. A format commonly used is the short form, a fixed-length measure in which all respondents complete the same items.3 Examples of PROMIS short forms include traditional short forms, profiles (eg, PROMIS-29, PROMIS-37), and the 10-item global health scale. Alternatively, PROMIS measures can be administered using item banks, a collection of items all measuring the same construct (eg, physical function). Item banks allow for customization for a specific patient population in the form of a computer adaptive test (CAT) (Figure 1) or the development of a custom short form.4,5

Figure 1. PROMIS CAT simulated administration

Custom short forms can use any items in the item bank, with patients, clinicians, and researchers selecting items with the most relevant content, and psychometricians validating the new measure.5 CATs can also use any items in the item bank. Utilizing item response theory, the selection of items is tailored for each respondent, ensuring high measurement precision across the spectrum of functioning and symptom severity within a patient population. Thus, CATs are brief, precise, and relevant to the respondent.3,4

One key difference between administering short forms and administering item banks such as CATs pertains to measurement precision. The degree of measurement precision with short forms is variable,3 potentially reducing their clinical relevance and interpretability. CATs offer a wider range of accurate scores and are less affected by floor and ceiling effects.6 Floor and ceiling effects refer to instances when >15% of respondents have the lowest or highest possible score, respectively. The presence of floor or ceiling effects suggests that items are missing at the lowest or highest ends of the PRO measure, thereby affecting reliability and validity.7 It is recommended that CATs be used over short forms when the patient population is in very poor health and when it is necessary to administer a smaller number of items.6 Both of these factors are important considerations when conducting rare disease clinical research.

With the solution suggested by the 2017 ISPOR report in mind, our objective was to review publications since 2017 to explore how PROMIS measures have been utilized in rare disease clinical trials with a specific focus on the use of PROMIS item banks compared with the use of PROMIS short forms.

"When designing clinical trials for a rare disease, an important consideration is that the outcomes are clinically relevant and interpretable."

What we found

PubMed was searched using the terms “patient-reported outcomes measurement information system,” “PROMIS,” and “clinical trial” for studies published between 2017 and 2022 describing rare disease clinical trials that included PROMIS measures as an outcome. The identified studies were reviewed independently by 2 of the authors, and data were extracted regarding which PROMIS measures were included as trial outcomes, how these measures were administered, and when the trial began (ie, before or after the July/August 2017 publication date of the ISPOR report). In addition, www.clinicaltrials.gov was searched to determine if any PROMIS publications that were automatically indexed to rare disease clinical trials had not been identified through the PubMed search.

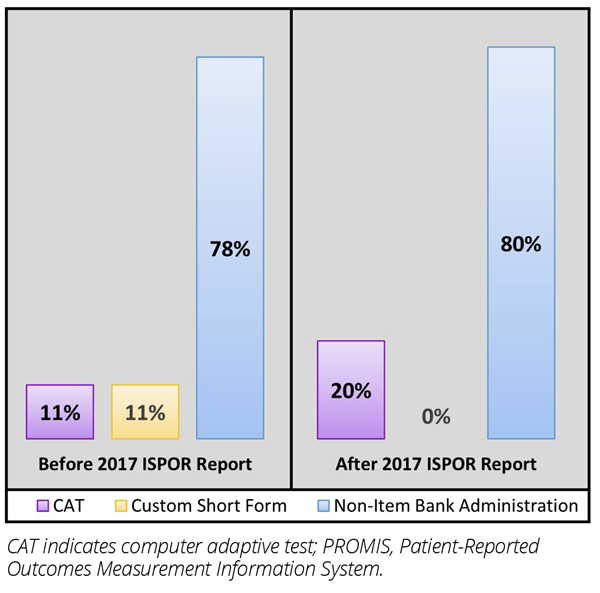

Our search yielded 36 relevant articles reporting on 30 different rare disease clinical trials. Although some clinical trials administered more than one type of PROMIS measure, the majority (80%) used only fixed-length short forms. Only 20% of trials utilized PROMIS item banks. Specifically, PROMIS CATs were administered in 4 trials, and in 2 trials, custom short forms were created for specific patient populations (eg, tenosynovial giant cell tumor, X-linked hypophosphatemia). In comparing trials that began before and after the publication of the ISPOR emerging good practices report, a small increase was observed in the proportion of PROMIS measures administered as CATs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PROMIS use before and after the release of the 2017 ISPOR emerging good practices report

Regarding the use of item banks in 6 of the 30 rare disease clinical trials, we took a closer look at what domains were assessed. The PROMIS domains administered via CATs illustrate the broad spectrum of HRQoL assessed in these rare disease clinical trials, including fatigue, physical function, pain interference, mobility, sleep disturbance, cognitive function, anxiety, depression, anger, peer relations, and ability to participate in social roles and activities. Of the 4 trials that administered PROMIS CATs, half also utilized the PROMIS 10-item global health scale, a fixed-length short form that broadly assesses HRQoL. The 2 trials that utilized item banks to develop custom short forms focused primarily on assessing the physical health dimension of HRQoL (eg, fatigue, physical function, pain interference).

"Establishing the value of a drug for a rare disease is difficult as traditional methods that focus on cost-effectiveness do not fully account for other factors such as the increased severity of the disease, the social value placed on incremental improvements in outcomes, and the lack of alternative treatment options."

Strengths and Limitations

This research is an early look at the impact of the 2017 ISPOR emerging good practices report. One of the purposes of the report was to recommend solutions that would increase PRO measure usage in rare disease clinical trials, thereby enhancing our understanding of treatment benefits from the patient’s perspective. We found that PROMIS item banks have been used in rare disease clinical trials, suggesting that this is a feasible option that may be on the rise. Of the 4 trials that administered PROMIS CATs, multiple CATs were utilized across various domains of HRQoL, gathering a substantial amount of information while keeping patient burden low. Additionally, our findings are consistent with other research showing that the use of CATs in clinical trials, in general, may be increasing over time.8

"Our objective was to review publications since 2017 to explore how PROMIS measures have been utilized in rare disease clinical trials with a specific focus on the use of PROMIS item banks compared with the use of PROMIS short forms."

The primary limitation of this research is that only published studies were examined. Our findings may not reflect the full picture of PROMIS utilization in rare disease clinical research because the publication of PRO results from clinical trials is often delayed or results are not published at all. It is critical that PRO results be included in peer-reviewed publications, and ideally reported with a trial’s primary endpoints as opposed to being reserved for a separate, later publication. Specifically, it is recommended that researchers make use of the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) PRO extension guidelines.9 This will allow for greater dissemination of PRO findings to patients and clinicians, thereby facilitating shared decision making. Another limitation is that our observation period from 2017 to 2022 may have been too short to detect changes in PRO measure administration and too early to witness the potential adoption of ISPOR recommendations made in 2017.

Conclusions

PROMIS item banks have been utilized in rare disease clinical trials both before and after the release of the 2017 ISPOR emerging good practices report, with a small increase in the proportion of PROMIS measures administered as CATs since the report was published. However, the primary mode of PROMIS administration remains the use of fixed-length short forms.

Challenges faced when trialing a new treatment for a rare disease have implications in subsequent health technology assessments to determine value and, ultimately, patient access.10 Establishing the value of a drug for a rare disease is difficult because traditional methods that focus on cost-effectiveness do not fully account for other factors such as the increased severity of the disease, the social value placed on incremental improvements in outcomes, and the lack of alternative treatment options.10 Health technology assessment agencies are modifying their methods for the evaluation of treatments for rare diseases, with the impact on HRQoL an important consideration for some.10

"Increased use of PROMIS item banks will enhance our understanding of health-related quality of life among patients with rare diseases."

Over time, increased use of PROMIS item banks will enhance our understanding of HRQoL among patients with rare diseases by providing more sensitive measurement of HRQoL while also reducing patient burden. Any improvement to the quality and precision of PRO inputs using PROMIS item banks that feed into health technology assessment will result in a more informed decision on the value of the treatment for patients and payers.

References

1. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on Clinical Trials in Small Populations. 2006. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-trials-small-populations_en.pdf

2. Benjamin K, Vernon MK, Patrick DL, Perfetto E, Nestler-Parr S, Burke L. Patient-reported outcome and observer-reported outcome assessment in rare disease clinical trials: an ISPOR COA Emerging Good Practices Task Force Report. Value Health. 2017;20(7):838-855. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.05.015

3. HealthMeasures. Differences between PROMIS Measures. HealthMeasures. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/differences-between-promis-measures

4. HealthMeasures. Computer Adaptive Tests (CATs). HealthMeasures. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/measurement-science/computer-adaptive-tests-cats

5. HealthMeasures. Make New PROMIS Measures. HealthMeasures. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/measure-development-research/make-new-promis-measures

6. Segawa E, Schalet B, Cella D. A comparison of computer adaptive tests (CATs) and short forms in terms of accuracy and number of items administrated using PROMIS profile. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(1):213-221. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02312-8

7. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34-42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

8. Smith AB, Hanbury A, Retzler J. Item banking and computer-adaptive testing in clinical trials: Standing in sight of the PROMISed land. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;13:005-5. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2018.11.005

9. Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814-822. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.879

10. Nestler-Parr S, Korchagina D, Toumi M, et al. Challenges in research and health technology assessment of rare disease technologies: report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Value Health. 2018;21(5):493-500. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2018.03.004

11. Tulsky DS, Kisala PA. An overview of the Traumatic Brain Injury-Quality of Life (TBI-QOL) Measurement System. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2019;34(5):281-288. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000531